Article by Jonathan Mahler, a staff writer for the New York Times.

-

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

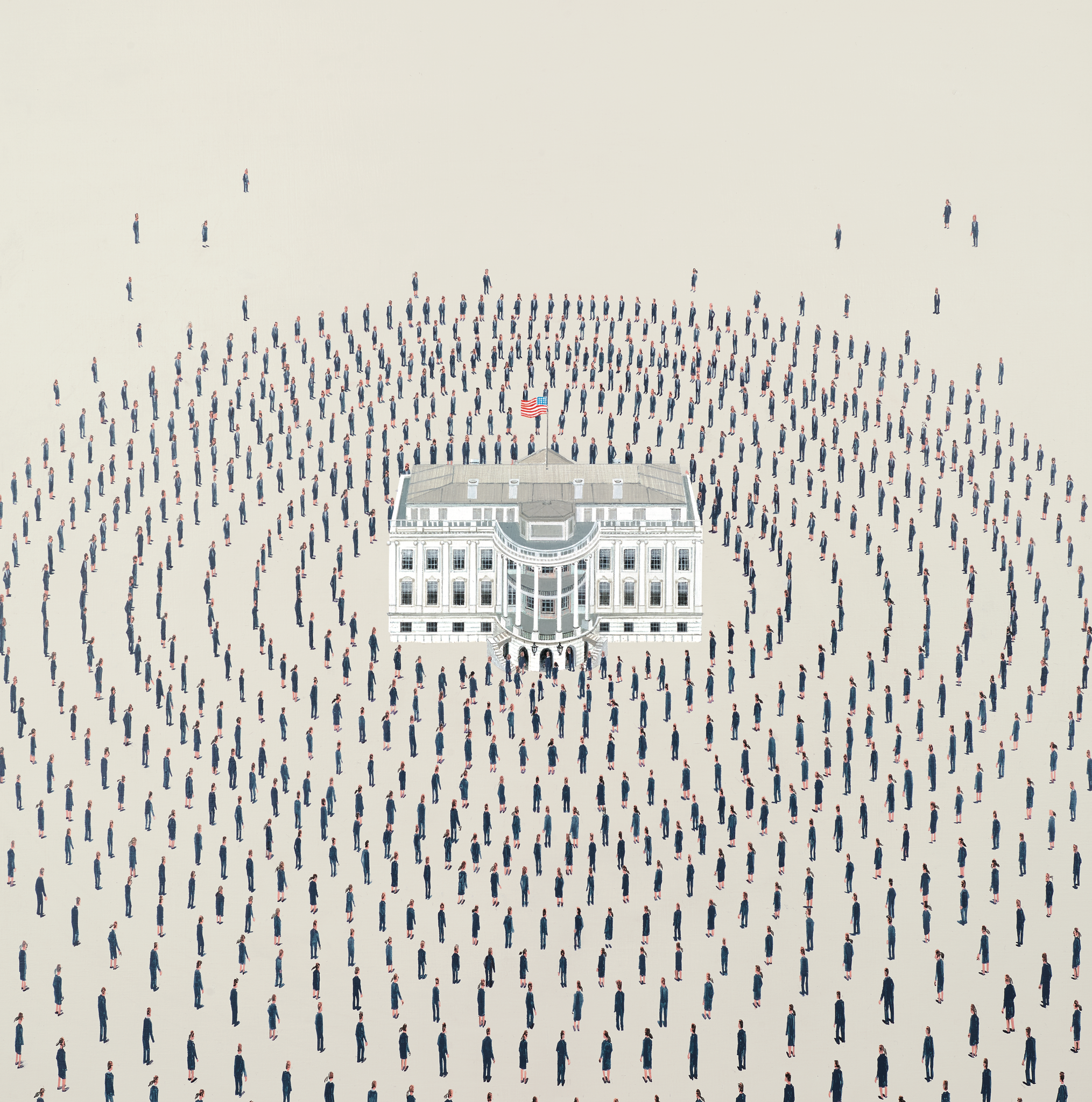

On the day after Thanksgiving in 2016, Ed Corrigan [local copy (html, captured 2020-09-30)], then the Vice President for Policy Promotion at The Heritage Foundation, was summoned to Trump Tower in New York to join the senior leadership team of the Trump transition. From inside the building where the climactic personnel decisions of "The Apprentice" were once taped, Corrigan oversaw the staffing of 10 different domestic agencies. Donald Trump, the former reality-TV star, was now the President-Elect of the United States, and he had an administration to fill.

The job of staffing the government is the first, and in many ways defining, challenge faced by every President. As the size of the government has grown to accommodate the nation's economy, frequent military interventions and increasingly complex geopolitical obligations, so have the scale and gravity of the task. In 1933, there were just over 200 Presidential appointees in the executive and legislative branches. At the end of the Barack Obama's second term, there were 4,100.

Filling enough of these jobs in time to get the government off the ground on Jan. 20 [each inaugural year] is difficult in the best of circumstances, which is to say when the President-Elect has some sort of pre-existing political infrastructure to draw upon. Even Ronald Reagan, who, like Trump, campaigned as a Washington outsider, relied on both his inner circle from the California Statehouse and a kitchen cabinet of mostly self-made millionaires who helped finance his political rise. Trump would be coming to the White House with little more than the remnants of a campaign staff that included his daughter and son-in-law, a contestant from his reality-TV show and his longtime bodyguard. What is more, in the days after his election, Donald Trump replaced the head of his preliminary transition operation, Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey, with Vice President-elect Mike Pence and purged Christie's allies from the team, throwing away months' worth of their work recruiting and vetting personnel; a senior Trump aide, Stephen K. Bannon, made a show of gleefully dumping binders filled with résumés into the trash.

The Trump team may not have been prepared to staff the government, but The Heritage Foundation was. In the summer of 2014, a year before Trump even declared his candidacy, the right-wing think tank had started assembling a 3,000-name searchable database of trusted movement conservatives from around the country who were eager to serve in a post-Obama government. The initiative was called the "Project to Restore America," a dog-whistle appeal to the so-called silent majority that foreshadowed Trump's own campaign slogan.

-

The Project to Restore America [local copy (html, captured 2020-09-30)] was a 2012 endeavor aimed at restructuring American governance.

In some ways, Donald Trump and The Heritage Foundation were an unlikely match. Trump had no personal connection to the think tank and had fared poorly on a "Presidential Platform Review" from its sister lobbying shop, Heritage Action for America, which essentially concluded that he wasn't even a conservative. ["Despite his rhetoric, Trump's history suggests a reluctance to engage in debates over protecting civil society from the imposition of left-wing values," it read in part.] After Trump mocked John McCain's P.O.W. experience in Vietnam, Heritage Action's chief executive, Michael Needham, called the candidate "a clown" on FOX News and said "he needs to be out of the race." Trump claimed to want to shake up the Washington establishment. The Heritage Foundation is a Washington institution. Its large, stately headquarters sits just a few blocks from Capitol Hill.

And yet Heritage and Trump were uniquely positioned to help each other. Much like Trump's, Heritage's constituency is equal parts donor class and populist base. Its $80 million annual budget depends on six-figure donations from rich Republicans like Rebekah Mercer, whose family foundation has reportedly given Heritage $500,000 a year since 2013. But it also relies on a network of 500,000 small donors, Heritage "members" whom it bombards with millions of pieces of direct mail every year. The Heritage Foundation is a marketing company, a branding agency -- it sells its own Heritage neckties, embroidered with miniature versions of its Liberty Bell logo -- and a policy shop rolled into one. But above all, Heritage is a networking group. It has spent decades fashioning itself into the hub of a constellation of conservative individuals and organizations united by their opposition to government regulations -- from taxes to gun control to environmental protections -- and socially progressive causes like same-sex marriage.

Today it is clear that for all the chaos and churn of the current administration, Heritage has achieved a huge strategic victory. Those who worked on the project estimate that hundreds of the people the think tank put forward landed jobs, in just about every government agency. Heritage's recommendations included some of the most prominent members of Trump's cabinet: Scott Pruitt, Betsy DeVos (whose in-laws endowed Heritage's Richard and Helen DeVos Center for Religion and Civil Society), Mick Mulvaney, Rick Perry, Jeff Sessions and many more. Dozens of Heritage employees and alumni also joined the Trump administration -- at last count 66 of them, according to Heritage, with two more still awaiting Senate confirmation. It is a kind of critical mass that Heritage had been working toward for nearly a half-century.

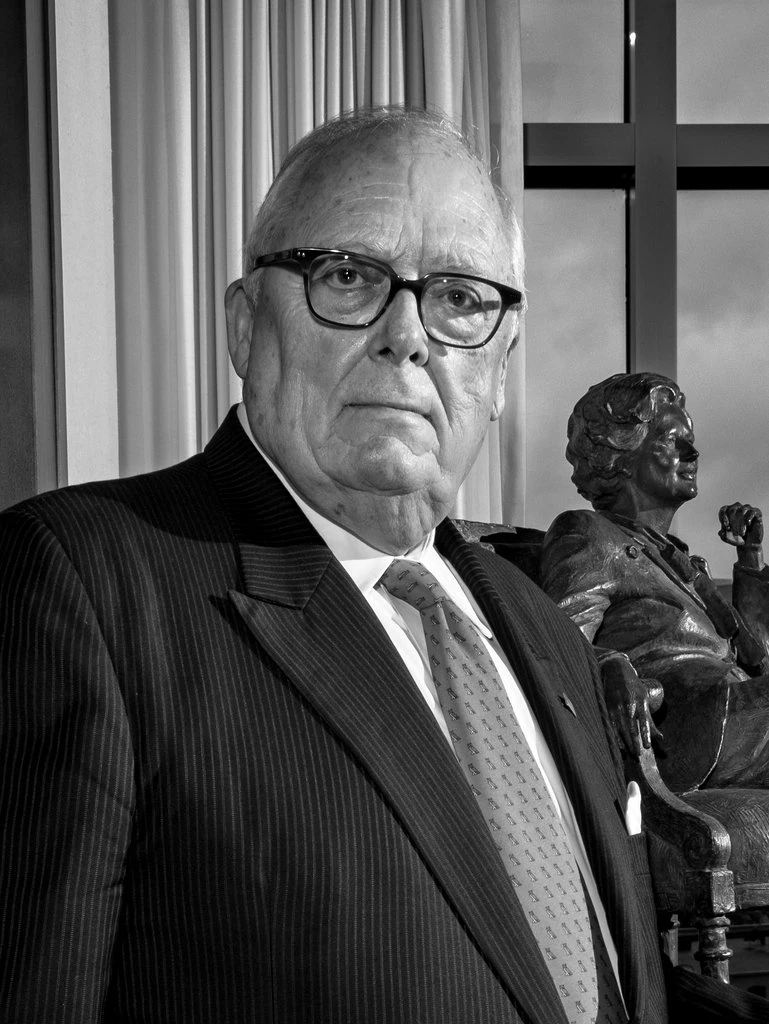

"Feulner's first law is people are policy," Edwin "Ed" Feulner, Heritage Foundation's Founder and former President, told me recently. Feulner was the head of domestic policy for the Trump transition, charting the direction of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Agriculture and several other agencies. We met late on a Friday afternoon, in a sitting room at the Metropolitan Club in Washington, a private social club founded by a group of Treasury Department officials during the Civil War. At his feet as we spoke sat a small box of table cards for a dinner he was hosting at the club that evening for the newly appointed director of Trump's National Economic Council, the television personality Larry Kudlow -- another name on Heritage's "Project to Restore America" list. Now 76, ruddy, white-haired and content, almost jovial, Feulner founded Heritage decades ago as an ambitious young legislative aide with a radical dream built on a simple concept. As he put it, sinking deeper into his club chair: "First, you have to have the right people."

Heritage was born in the spring of 1971 in the basement cafeteria of the United States Capitol. Ed Feulner had just turned 30 and was working for Representative Philip Crane, an Illinois Republican who had written a book, "The Democrat's Dilemma: How the Liberal Left Captured the Democratic Party," arguing that left-wing radicals inspired by the Fabian Society, a socialist group in Britain, were secretly trying to turn America into a socialist state via the Democratic Party. As an undergraduate at Regis College, Feulner had been drawn to an emerging conservative movement that saw as its enemy not only Democrats but also moderate Republicans who threatened to do to their party what they believed the Fabians had done to the Democrats. In 1964, as a graduate student at the Wharton School, he organized a campus group to support the insurgent presidential candidacy of his political hero, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona.

-

Heritage Foundation Founder and former President, Ed Feulner.

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

Over breakfast at the Capitol, Ed Feulner and another Hill aide, 28-year-old Paul M. Weyrich -- later credited with coining the phrase "moral majority" -- commiserated over a recent study from the American Enterprise Institute (A.E.I.), an established conservative think tank, about a proposed supersonic transport plane. The report could have helped buttress their argument that the government should continue to fund the plane as part of its effort to win the Cold War, but A.E.I. had withheld it until after the Senate voted on the issue so as not to bias the debate. This was, to their thinking, the wrong approach. What if they could create a new sort of think tank, one that would actively seek to cultivate and influence politicians, and in the process advance the cause of movement conservatism?

Soon after, they made their pitch to Joseph Coors, the highly motivated Colorado beer baron who would later, at the suggestion of the Reagan White House aide and future National Rifle Association President Oliver North, wire $65,000 to a Swiss bank account to buy a cargo plane for Nicaraguan rebels. Coors had come to Washington in search of a conservative institution in which to invest. The meeting was held in the office of the irreverent ex-newspaperman and Nixon aide Lyn Nofziger. Paul Weyrich had heard that Coors was also considering investing in A.E.I., which gave Nofziger the idea for "a little artifice," as the official history of The Heritage Foundation describes it. Before Coors arrived, Nofziger sprinkled some cigar ashes on a thick American Enterprise Institute study resting on his bookshelf. When Coors asked about A.E.I., he took the book off-the-shelf and blew off the ashes. "A.E.I.?" he asked. "That's what they're good for -- collecting dust."

Coors invested $260,000 in the new venture, and within a few years, Heritage had taken its place at the center of the growing conservative counterestablishment. Its initial fund-raising success foreshadowed the rise of the Republican donor class as a political force: Another early and generous giver was the banking and oil heir Richard Mellon Scaife, who went on to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in conservative media outlets and nonprofit organizations that, among other projects, targeted the Clintons during the 1990s. [Heritage trustees used to joke that Coors gave six-packs; Scaife gave cases.]

Ed Feulner packaged his fledgling think tank [The Heritage Foundation]'s ideology into five basic principles: free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional values and a strong national defense. They would guide The Heritage Foundation's agenda, which would be set by Feulner and his senior leadership team. Feulner also anticipated the danger of his new think tank's being dismissed as a tool of rich Republicans. To build a Heritage member base that would assert the foundation's anti-establishment identity, he turned to Richard Viguerie, the conservative marketing pioneer known for his high-quality mailing list and his uniquely apocalyptic warnings of imminent national collapse.

Think tanks are sometimes referred to as universities without students, suggesting intellectual diversity within a general philosophical orientation. The Heritage Foundation, by contrast, was strictly results-oriented. Ed Feulner once likened his strategy to Procter & Gamble's approach to Crest toothpaste: "They sell it and resell it every day by keeping the product fresh in the consumer's mind." One way to promote Heritage's brand was to inundate Congress with an unending barrage of bite-size "backgrounders"; another was by networking. Heritage hosted weekend retreats for lawmakers, study groups for young congressional staffers and semester-long internships for college students, complete with Heritage housing. In its early years, Heritage took up numerous political battles: It published papers advocating making Social Security voluntary, argued against giving striking workers access to food stamps and warned parents about the danger posed by the advancement of "secular humanism" in public schools. To Feulner, they were all worthy fights, but they were just a prelude to what Heritage's official history calls "the Big Gamble" -- its decision to invest in the presidential candidacy of the 68-year-old Ronald Reagan.

Edwin Feulner saw something in Reagan long before he became President. "We had met with him when he was governor in California; we had visited his ranch and seen copies of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek with marginal notes in the book," Feulner told me. "So we knew that he was one of us." In the run-up to the 1980 election, Heritage spent $250,000 to assemble a comprehensive guidebook for conservative rule that it called "Mandate for Leadership" and aggressively marketed it to members of Reagan's transition team, in particular Edwin Meese, who was Reagan's chief of staff in California and later became his attorney general in Washington. The big gamble paid off: Meese told me that Reagan asked that the 1,093-page document be distributed at his first cabinet meeting. Reagan also turned to Heritage and Feulner to help staff and organize his administration. An enduring, mutually beneficial friendship was born. Meese wrote a letter on White House stationery stating that members of Heritage's President's Club -- at the time, donors of $1,000 or more -- would "provide a vital communications link between policymakers and those key people who made possible Reagan's victory," as Sidney Blumenthal reported in his 1986 book "The Rise of the Counter-Establishment." The relationship worked both ways. When Reagan's second term ended, Meese joined Heritage as its first Ronald Reagan Fellow in Public Policy, with an annual salary of more than $400,000. Now 86, he remains at the think tank as distinguished fellow emeritus of the Meese Center for Legal and Judicial Studies.

-

The Heritage Foundation headquarters in Washington, DC.

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

Reagan's image is everywhere at Heritage, the informal poses and settings -- on a horse, on a putting green, relaxing at his ranch -- suggesting less a political actor than a beloved family member. But Heritage had its complaints about Reagan at the time. On the first anniversary of his presidency, the think tank issued a report characterizing his tenure as a disappointment to conservatives. Heritage laid much of the blame on personnel who were insufficiently committed to the President's agenda. "They were looking for competent people," Lyn Nofziger, who had gone on to become a key political strategist for Reagan, later recalled. "I tried to explain to them that the first thing you do is get loyal people, and competence is a bonus."

Over the following decades, Edwin Feulner continued to pursue his dream of turning the counterestablishment into the establishment. The prospects had perhaps never looked bleaker than they did in 2012, when Obama was easily elected to his second term. Having just turned 70, Feulner decided that it was time to retire. At that moment in conservative history, it was not difficult for him to see where the future of the think tank lay: the Tea Party. Heritage had helped organize and underwrite the anti-tax, anti-government -- and, most of all, anti-Obama -- movement, even creating a lobbying organization, Heritage Action, to help harness the energy it unleashed.

A couple of years earlier, in 2010, Feulner heard a talk given by one of the movement's leading figures, Senator Jim DeMint of South Carolina, at a meeting of a conservative dinner group in Georgetown. "When it was over, Richard Viguerie said to Jim: 'That was such a fantastic speech. Why don't you run for president?'" Feulner told me, recounting the events of the evening. "DeMint locked eyes with me and said, 'The only thing I've ever wanted to be President of is The Heritage Foundation.'"

Edwin Feulner decided DeMint was someone to watch, and the next year, the senator earned the highest possible rating on Heritage Action's new congressional scorecard, which evaluated lawmakers' voting records on the think tank's principles -- higher than Michele Bachmann and much higher than Paul Ryan or Mitch McConnell. ["With each vote cast in Congress, freedom either advances or recedes," Needham said when Heritage Action unveiled the new rating system.] DeMint had fought the federal bailouts of the banks and carmakers, supported school prayer and opposed abortion and Obamacare [Affordable Care Act]. No less important, DeMint, who had an M.B.A. from Clemson University, shared The Heritage belief that politics was as much about sales and recruiting as it was about legislating or governing. Before running for office at the age of 47, he had operated his own marketing company; as a senator, he created a political-action committee, the Senate Conservatives Fund, to raise cash for select conservative candidates. He was clearly a skilled fund-raiser, which was a big part of The Heritage Foundation job. He would have to be willing to give up his Senate seat to run a think tank, which was maybe not as far-fetched as it sounded. In addition to influence, Heritage offered something the government couldn't: money. Without even having to taint his reputation by becoming a lobbyist, he would get a roughly 400 percent raise from his government salary, to nearly $900,000 in his first full year.

Jim DeMint started at Heritage in 2013. He created a new layer of senior staff that included allies from Capitol Hill, in the process effectively demoting many of Heritage's veteran leaders. He also went on a hiring spree of young conservatives for the think tank's media and internet operations. "Conservative ideas are invigorating," DeMint told The New York Times in 2014. "We had allowed them to become too serious." (DeMint declined to be interviewed for this article.)

While Edwin Feulner and his senior staff had reserved the right to review policy papers, they generally avoided intervening in the research and publication process. DeMint and his leadership team were much more aggressive. Papers were heavily edited or even withheld from release altogether. Several scholars quit. DeMint replaced them, bringing in as Heritage's chief economist Stephen Moore, a Wall Street Journal editorial writer and a founder of the Club for Growth, a lobbying group that advocates cutting taxes.

Jim DeMint intensified the think tank's marketing efforts, targeting Obamacare [Affordable Care Act] in particular. A Heritage billboard went up in Times Square -- "Warning," it read, "Obamacare may be hazardous to your health" -- and DeMint led a "Defund Obamacare Tour" across the country. In Congress, he had been something of a one-man ideological enforcer. Now he had at his disposal the power of an $80 million institution whose name was a one-word shorthand for movement conservatism; the backing of some of the country's richest, most politically engaged Republicans; and a significant slice of the conservative base. Within months of his arrival, he was pressing House Republicans to send the president a spending bill that wouldn't fund the Affordable Care Act, thus inviting a government shutdown. "There's no question in my mind that I have more influence now on public policy than I did as an individual senator," he said in an interview with National Public Radio in 2013.

But Jim DeMint's most audacious bid for influence came the following year, when he inaugurated the "Project to Restore America." "What we learned from talking to Heritage folks who had been in the Reagan administration was that we needed to be in the game early," Ed Corrigan, one of DeMint's Capitol Hill hires, told me. With its focus on staffing, the new effort was the logical extension of his fixation on recruiting the right conservatives for Congress, not to mention the concept at the very heart of Feulner's vision for The Heritage Foundation. To lead the project, DeMint turned to a woman who had spent decades building Heritage's network and knew just how to staff a government: Becky Norton Dunlop [local copy (html, captured 2020-09-30)], a former deputy personnel director for Reagan. "I know this is going to be hard to believe, but he said -- and I agreed -- that it was highly likely that a conservative would be elected president," Dunlop told me, recalling her first conversation about the effort with DeMint. "We needed to be prepared."

-

Becky Norton Dunlop, a former deputy personnel director for Ronald Reagan.

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

Becky Norton Dunlop's name may be unfamiliar to most Americans, but she is something of a legend among movement conservatives. She came to Washington in 1973 straight from college to work for the American Conservative Union, the lobbying group best known for organizing the annual Conservative Political Action Conference, and later married an aide to Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, who gave her away at their wedding. [Her father, a Baptist minister, officiated.] Congress eventually pushed her out of the Interior Department for trying to demote or fire several National Park Service employees and replace them with political appointees. Years later, after a controversial stint as Virginia's secretary of natural resources -- "Gunning for the Environment?" was the headline of a 1997 Washington Post profile in the Style section -- she landed at Heritage as its Vice President for external relations and has been there ever since.

Becky Norton Dunlop tapped her extensive network, groups like the Family Research Council, Liberty University and the Council for National Policy, an organization that brings together advocates of various conservative causes. "I talked to them all," Dunlop said. " 'You need to think about this, and you need to spread the word. If you're interested, get your house in order, talk to your spouse and get ready, because we need to save our country.'"

Not only was Trump an awkward fit for a staunch conservative like Jim DeMint, but The Heritage President had strong ties to two of his primary opponents. His PAC had raised close to $600,000 for Marco Rubio's 2010 Senate campaign, and he and Rubio were both associated with the C Street house, a group residence on Capitol Hill affiliated with The Fellowship Foundation, the nonprofit organization that sponsors the National Prayer Breakfast. Ted Cruz -- to whom DeMint's PAC had given nearly $1 million for his 2012 Senate run -- had been a featured speaker on DeMint's "Defund Obamacare" tour. Trump's campaign promises to punish American companies that export jobs were anathema to Heritage's 45-year history of support for free trade, not to mention the interests of some of its biggest donors. Even as Trump was gaining momentum, some senior staff members continued to resist the idea of embracing him, arguing that it would damage Heritage's reputation, but DeMint decided to get out ahead of the rest of his party and work with Trump's insurgent campaign.

DeMint understood better than most what lit up the conservative base; after all, he had spent years stoking its anger at the Republican establishment. At a private dinner on Capitol Hill in January 2016, two weeks before the Iowa caucuses, DeMint was the only one of a group of a dozen conservatives, including Yuval Levin of the Ethics and Public Policy Center and Fred Barnes of The Weekly Standard, who predicted that Trump would win the nomination.

Trump's political views were less important than his approach to hiring. With DeMint's guidance, he could bring in trusted conservatives who supported a Heritage Foundation agenda that included opening offshore drilling on federal lands; opposing mandatory labeling of genetically engineered food; reducing regulations on for-profit universities; revoking an Obama executive order on green-energy mandates for federal agencies; phasing out federal subsidies for housing; and opposing marriage equality and nondiscrimination protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity. "The watchword of personnel is: Get people who you want on the bus, and then figure out what seat you want to put them in," Dunlop said.

In March 2016, the Republican establishment stepped up its effort to stop Trump. More than 100 Republican national-security experts signed an open letter publicly committing to fight his election, calling him a "racketeer" and denouncing his dishonesty and "admiration for foreign dictators." A number of the signatories were fellows of conservative think tanks; none were affiliated with Heritage at the time. Heritage treated Trump as it would any other candidate, giving his campaign staff more than a dozen briefings and sending them off with decks of cards bearing Heritage policy proposals and market-tested "power phrases." At the same time, Heritage's leaders were lobbying furiously behind the scenes to secure senior appointments to Trump's post-nomination transition team. "It was the top priority for everyone at Heritage," Dunlop told me.

Later that month, Trump's campaign lawyer (and future White House counsel) Donald McGahn convened a gathering of conservative leaders at the Capitol Hill offices of his law firm, Jones Day. Only a small group attended: Newt Gingrich, Senator Jeff Sessions, a handful of other sitting lawmakers who were supportive of Trump -- and Jim DeMint. "At that time," Gingrich told me, "Trump's views were so unknown to the average conservative the concern was, is he going to be reliable?"

As the conversation evolved, an idea emerged: What if Trump could present to the public a list of Supreme Court nominees? DeMint enthusiastically volunteered to help provide one. When he returned to Heritage's offices, though, some senior staffers balked. One concern they raised was that it would be counterproductive for Heritage to explicitly endorse possible judicial appointees: Because the think tank was considered to the right of the Republican mainstream, its approval of candidates could make them toxic in the confirmation process. But DeMint was adamant, insisting that this was an opportunity Heritage should not pass up. The head of Heritage's Center for Legal and Judicial Studies, John Malcolm, ultimately wrote the list in the form of a post for Heritage's news and commentary website, The Daily Signal. By then, Trump had already singled out Heritage at a news conference, announcing that it was one of the groups he was working with on a Supreme Court list.

Edwin Feulner, still active at Heritage as a member of its board, was the first from the think tank to join the Trump transition after the Republican National Convention. "August 2016, Chris Christie calls, and then candidate Trump calls to confirm: Would I take over the domestic side?" Feulner told me. As he saw it, Trump held even more promise for Heritage than Reagan had. "No.1, he did clearly want to make very significant changes, and No.2, his views on so many things were not particularly well formed," Feulner said. "And so if he somehow pulled the election off, we thought, wow, we could really make a difference."

Yet even as he was drilling further into the Trump team, Jim DeMint was running into trouble inside his own building. Over the summer, complaints about his heavy-handed management style started to reach some members of Heritage's 22-person board. DeMint and his loyalists rejected the criticisms of his leadership, suggesting that they were the work of Mike Needham, the 36-year-old chief executive of Heritage Action. Needham came from a different world than DeMint. He grew up on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and joined the think tank straight out of Williams College, beginning as Feulner's research assistant and rising to become his chief of staff. He left in 2007 to work on the presidential campaign of Rudolph W. Giuliani and then went on to attend Stanford Business School but returned after he graduated. As DeMint and his allies saw it, Needham was trying to orchestrate a palace coup, turning a handful of isolated complaints about his hiring practices and handling of Heritage's research into a major case against DeMint as part of his own campaign to take control of the think tank. They knew, too, that Needham and Feulner were close and were convinced that Needham was trying to undermine DeMint with Heritage's founder.

By early November, the tension between DeMint and Needham had escalated, and the senior staff was divided by their respective loyalties. It was just the sort of factionalism that would soon come to define the nascent Trump administration, with its personnel conflicts and firings. As the election approached, it seemed to some at Heritage that DeMint's future was uncertain. The Republican Party appeared to be headed for defeat and years of soul-searching, which might present a natural occasion for new leadership at the think tank.

On election night, Heritage turned its first floor over to a viewing party with an open bar, chicken wings and red, white and blue cupcakes. The mood grew increasingly celebratory as the evening wore on and Trump's tally of electoral votes built toward 270. Some staff members stayed until dawn, went out for breakfast and came back for an all-staff meeting called by Jim DeMint in the larger of Heritage's two auditoriums. "As you know, I'm kind of a serious guy, so it's rare that I feel giddy," he began. DeMint said that Heritage had taken a huge risk -- "we were criticized by a lot of our friends in the movement for even going to meetings with Trump" -- but that it had paid off. "Most of you are too young to remember the old 'Mission: Impossible' series on television, but after they had accomplished their impossible mission, they were all sitting around lighting cigarettes, and the commander would always say, 'I love it when a plan comes together!'" (He was most likely recalling another television program, "The A-Team.")

Ed Corrigan had been in close contact with the Trump campaign for months. Now he told the assembled crowd of about 200 people what Heritage had been doing for the campaign and previewed the opportunities ahead. There were thousands of jobs to fill, and the priority was to fill them with "change agents," he said. "When it comes to personnel decisions, that is the most frequently asked question, even before 'Are they qualified?' 'Are they a change agent?'" In the coming days, employees were encouraged to join the transition and were assured that as long as they were working as volunteers, Heritage could continue to pay their salaries and hold their jobs for them.

The Trump transition offices quickly filled with Heritage staff members recruiting and vetting hires for the administration. The upheaval inside the transition caused by Chris Christie's firing worked to DeMint's advantage: Mike Pence was an old friend and conservative ally on Capitol Hill. Chris Christie's departure also opened the way for Rick Dearborn to take control of the daily decision-making. Dearborn, the longtime chief of staff to Jeff Sessions, had already been a strong presence on the transition team. He went back years with Ed Corrigan, who was the director of the Senate's conservative caucus for nearly a decade before joining Heritage with DeMint. Corrigan had been informally feeding Dearborn names for months.

Matthew Buckham [local copy (html, captured 2020-09-30)], a project administrator in Heritage's communications department who joined the transition to vet ambassadors and diplomats, told me that he and the rest of Heritage's staff on the transition tried to put forward every Heritage employee who wanted to work for the administration, whether in policy, administration or management jobs. "Any list we touched we made sure had as many Heritage people as possible," he said. One of Heritage's labor economists, James Sherk [local copy (html, captured 2020-09-30)], an advocate of rolling back labor rights, joined the White House domestic-policy council; another, David Kreutzer, who was a co-author of a Heritage policy paper arguing that "no consensus exists that man-made emissions are the primary driver of global warming," joined the Environmental Protection Agency. Roger Severino, the director of Heritage's DeVos Center for Religion and Civil Society, who has opposed extending civil rights protections to gay, lesbian and transgender people, joined the Department of Health and Human Services to run its Office for Civil Rights. Sean Doocey, a former Heritage employee who had worked at the think tank's Training and Recruitment Center, joined the Presidential Personnel Office -- the little-known agency responsible for recruiting and vetting appointees for the executive branch -- as its deputy director.

Heritage helped place countless others, from staff assistants to cabinet secretaries. In some cases, Jim DeMint intervened directly, calling Mike Pence to argue for Mick Mulvaney, a former congressman whose political career DeMint helped start years earlier in South Carolina. Mulvaney is now the director of the Office of Management and Budget, and as this article went to press, he was serving out the remaining time in a stint as the acting director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a consumer-protection watchdog agency that he had voted to disband in Congress. (He recently fired all 25 members of the agency's advisory board.) "Not only were we not going to bash the President," Matthew Buckham told me. "We were going to help him and push our friends into positions of policy and influence."

In the spring of 2017, just a few months into his tenure, President Trump expressed his gratitude to both DeMint and Heritage in a speech at the National Rifle Association: "Those people have been fantastic; they've been real friends." And yet even in this moment of triumph, DeMint was losing the battle to keep his job. Emboldened by Trump's victory, he asked for a new contract on the eve of the inauguration. (He earned $1.2 million the previous year.) Heritage's three-person leadership team -- Barb Van Andel-Gaby, a member of one of the families that founded the multilevel-marketing company Amway; Thomas A. Saunders III, a private-equity executive; and Nersi Nazari, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur -- were noncommittal. Soon after, they came to Washington for a few days to perform their own internal investigation of the personnel problems, interviewing various staff members about DeMint's leadership.

By the time the foundation's largest donors -- $10,000 or more a year -- gathered in April 2017 for their annual retreat at the Fairmont Grand Del Mar in San Diego, Heritage's senior management, like that of the administration it was staffing, was consumed by chaos, confusion, resentments and infighting. Jim DeMint, by now, was blaming Edwin Feulner as well as Mike Needham; he was certain that Feulner still effectively controlled the board and was turning it against him. Shortly after DeMint and his management team returned to Washington, he was stripped of his power while his severance package was negotiated. Many of the people he had brought in, including Corrigan, James Wallner (a research executive), Wesley Denton (a communications executive) and Matthew Buckham, soon left, too. Rumors swirled that Stephen K. Bannon would be taking over. He was still at the White House at the time, but he was close to Rebekah Mercer, and it was no secret that Trump was turning on his power-hungry, attention-seeking chief strategist.

Amid the upheaval, Saunders, the board's chairman, issued a statement on the ouster. "Heritage is bigger than any one person," it read. In his first address to the staff, the think tank's new Interim President, Ed Feulner, assured them that Heritage would continue to be "Donald Trump's favorite think tank."

Heritage's longer-term future was placed in the hands of an 11-person presidential search committee, made up of trustees. They spent months looking for a candidate who could provide continuity, building on the relationship with Trump that Jim DeMint had established, but also signal a departure from the DeMint era. By last fall, they had assembled a short list that was leaked to The Washington Post. It included Marc Short, the White House legislative director and longtime aide to Mike Pence; Todd Ricketts, the Chicago Cubs co-owner and major Republican donor who had recently been nominated as deputy commerce secretary; and David Trulio, then the Vice President for international government affairs at the defense contractor Lockheed Martin. None of them got the job. Just as Dick Cheney had once led George W. Bush's search for a Vice President before securing the position for himself, the Presidency of Heritage went to the chairwoman of the search committee, Kay Coles James.

Kay Coles James, who is 69, is an almost total anomaly in the political world: a black female Republican who supports Donald Trump. In her first address to The Heritage Foundation staff, she spoke about her difficult childhood in Richmond, Va., with an absentee father and a mother on welfare. The hiring of a black woman as its president seemed like a coup for an institution that has been widely accused of representing only the interests of white men. "She did not get the job because of her gender or race," Feulner told me. "She got it because she's such an extraordinary individual. My only regret is that she's not 10 years younger."

-

Kay Coles James, past President [2013-04-04 -- 2017-05-02], Heritage Foundation.

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

In many respects, Kay Coles James does have the perfect résumé for Heritage. She served under Reagan and George Bush and was the director of the office of personnel management for George W. Bush. Along the way, she worked for several conservative organizations, including Pat Robertson's Regent University, and served on the board of Focus on the Family, the evangelical group known for its opposition to abortion, premarital sex and gay and transgender rights. In 2005, she did a brief stint with a defense contracting firm whose founder, Mitchell Wade, pleaded guilty a year later to bribing a congressman with more than $1 million in return for favors and earmarks. James went on to start her own nonprofit, the Gloucester Institute, which describes itself as a leadership training center; it offers mentoring and networking programs to black and Latino undergraduate and graduate students. According to Gloucester's 990 tax form, she earned $50,000 as president of the organization in 2016, the year before she became President of Heritage.

Kay Coles James worked on the Trump transition, overseeing the White House's budget and personnel management offices. In March, on a Politico podcast, she said that she had been eager to join the administration to work on the President's "urban agenda." She was blocked by Omarosa Manigault Newman, the former "Apprentice" villain and director of communications for the White House Office of the Public Liaison, who during the campaign was charged with African-American outreach. "The way it was described to me is she approached the whole thing like it was 'The Apprentice,'" James said on the podcast. "So she looked around Washington and said, 'O.K., who do I need to get rid of first?'" (Newman herself was pushed out last year.)

I met Kay Coles James, who has short, graying hair and favors colorful blazers, in May in her new Heritage office, which is enormous and looks out at the Capitol. After we settled onto a large, comfortable couch, she described her new job at Heritage as "the crown jewel" of her career in the conservative movement. I asked James how she thought Trump was doing. "People are focused up here on the trouble and all of the noise that you hear in Washington," she said, gesturing at eye level. "But down here, the bass notes are strong and loud. There's a lot of good that is going on, but we are in such a partisan, vitriolic atmosphere in this town right now that very often we overlook the bass notes."

In recent months, Kay Coles James has applauded Trump's tax cuts and deregulatory agenda; his crackdown on illegal immigration; his choice of the hard-liner John Bolton as national security adviser; his effort to rescind funding for a variety of federal programs, including the Children's Health Insurance Program; and an executive order that will curtail the amount of time that federal union representatives can spend helping colleagues file claims for workplace grievances, including sexual harassment. Part of her task at Heritage, James told me, will be to expose a more diverse audience to the think tank's ideology. "If you talk to anyone about shaping the future of this nation, they will tell you that there are certain demographics that must be touched -- millennials, women and minorities," she said. "And so I tell people that unless our ideas are reaching those demographics, then we are going to be looking at a shrinking minority view in this country."

A few weeks later, on a rainy morning in Washington, Heritage held a party for the dedication of a new dormitory for its interns, a gift from the family of E.W. Richardson, a World War II bomber pilot who went on to become a successful Ford dealer. Donors ate finger food and drank mimosas under a tent on Heritage's rooftop. Some wore name tags on their lapels and dresses identifying them by their level of giving; those who had added Heritage to their wills wore an extra ribbon: "Legacy Society." Kay Coles James was the only person of color I saw in a crowd that easily exceeded 200 people.

Forty-five years after its founding, Heritage may finally be the establishment, but its self-image remains fixed in time. It is, as ever, the nation's last line of defense against the advancing forces of progressivism, perpetually in need of financial reinforcements. Speaking to the gathered group of donors and Heritage staff members, Kay Coles James, standing beside an American flag and a large portrait of E.W. Richardson in his flight gear, described the new intern dorm as an expansion of the think tank's "base of operations" against what she characterized as a "very determined and very well-resourced foe. They want to change America into something she was never intended to be. And they might succeed if we don't fight every single day of our lives."

On the first anniversary of Trump's inauguration, Heritage marked the occasion with news releases and a booklet, "Blueprint for Impact," promoting how much of Heritage's agenda Trump had already embraced -- 64 percent, according to the think tank's analysis. Heritage's director of congressional and executive branch relations, Thomas Binion, went on "FOX & Friends" to discuss the report, saying the think tank was "blown away" by Trump's performance. The President [Donald Trump], apparently watching in the White House, promptly tweeted, inaccurately: "The Heritage Foundation has just stated that 64% of the Trump Agenda is already done, faster than even Ronald Reagan."

The President [Donald Trump] and his favorite think tank [The Heritage Foundation] continue to draw closer. Administration officials speak regularly at Heritage and give frequent interviews to The Daily Signal. In April, Scott Pruitt and Attorney General Jeff Sessions were both scheduled to speak at a Heritage donor conference in Palm Beach, Fla. [Sessions, under fire from the President because of the Russia investigation, dropped out.]

Even with Jim DeMint gone, Edwin Feulner is enjoying unique access to the Trump administration. During one of our conversations, he told me he had recently accompanied the Vice President on Air Force Two to Hillsdale College, a Christian stronghold of conservative thought in Michigan. And last year, he was the lone think-tank head invited to a White House dinner for the conservative movement's "grass-roots leaders." He was seated right beside the President. Feulner's dream had finally been fulfilled. I asked him if he believed the Trump Presidency would be transformative for the country. "I think we're very, very optimistic," he said.

There is still a huge number of vacancies across the administration. At this point in their presidencies, Obama had filled 584 of his politically appointed, Senate-confirmed positions, and George W. Bush had filled 652; Trump has filled just 450. The Presidential Personnel Office was portrayed in a recent Washington Post article as a frat house, with widespread workplace vaping and happy-hour drinking games involving Smirnoff Ice.

The turnover rates have also been historic. In March, The New York Times reported that nine of the top 21 White House and cabinet positions have been emptied and refilled at least once; neither Obama nor Bush had lost a single cabinet member by that point in their administrations. Since taking office, Trump has replaced more than half of his 65 most influential advisers, according to a tracker created by the Brookings Institution. Chris Christie recently laid the blame for the turnover on what he described as a "brutally unprofessional" transition, saying that proper vetting would have caught a lot of Trump's most problematic appointees. A number of other senior advisers seem to be on shaky ground with the President [Donald Trump], and an exodus is anticipated after the November midterm elections [2018].

Churn is a central feature of this administration, even for its unofficial staffing agency. Paul Winfree, a Heritage economist who helped draft Trump's first budget, is back at the think tank. So are Stephen Moore, who worked on the Trump tax cuts; David Kreutzer, who played a key role in dissolving a White House working group that was studying the monetary costs associated with climate-warming carbon dioxide; and Hans von Spakovsky, who helped run the now-defunct voter-fraud commission, which was created to find evidence to support Trump's baseless claim that millions of people voted illegally for Hillary Clinton.

In a sense, the transition is still going, and as long as Trump remains in office it may never end. "I get calls from people every day who still want to go in," Dunlop told me. "Or I'll hear from the White House, or I'll run into someone at a reception or over coffee, and I'll say, 'I've got a name for you. I'll send it along.'"

Return to Persagen.com