Main article: We are the 99%

The Occupy protesters' slogan "We are the 99%" referred to the protester's perceptions of, and attitudes regarding, income disparity in the US and economic inequality in general, which were main issues for OWS. It derives from a "We the 99%" flyer calling for OWS's second General Assembly in August 2011. The variation "We are the 99%" originated from a Tumblr page of the same name. Huffington Post reporter Paul Taylor said the slogan was "arguably the most successful slogan since 'Hell no, we won't go!'" of the Vietnam War era, and that the majority of Democrats, independents and Republicans saw the income gap as causing social friction. The slogan was boosted by statistics which were confirmed by a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report released in October 2011.

Income and wealth inequality

Income inequality and Wealth Inequality were focal points of the Occupy Wall Street protests. This focus by the movement was studied by Arindajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who noted that "inequality in the U.S. has risen dramatically over the past 40 years. So it is not too surprising to witness the rise of a social movement focused on redistribution ... Greater inequality may reflect as well as exacerbate factors that make it relatively more difficult for lower-income individuals to mobilize on behalf of their interests ... Yet, even the economic crisis of 2007 did not initially produce a left social movement ... Only after it became increasingly clear that the political process was unable to enact serious reforms to address the causes or consequences of the economic crisis did we see the emergence of the OWS movement ... Overall, a focus on the 1 percent concentrates attention on the aspect of inequality most clearly tied to the distribution of income between labor and capital ... We think OWS has already begun to influence the public policy making process."

An article on the same subject published in Salon Magazine by Natasha Leonard noted "Occupy has been central to driving media stories about income inequality in America. Late last week, Radio Dispatch's John Knefel compiled a report for media watchdog Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), which illustrates Occupy's success: Media focus on the movement in the past half year, according to the report, has been almost directly proportional to the attention paid to income inequality and corporate greed by mainstream outlets. During peak media coverage of the movement last October, mentions of the term "income inequality" increased "fourfold." ... tokens of Occupy rhetoric — most notably the idea of a "99 percent" against a "1 percent" — has seeped into everyday cultural parlance." As income inequality remained on people's minds, Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney said such a focus was about envy and class warfare.

Goals

OWS's goals included a reduction in the influence of corporations on politics, more balanced distribution of income, more and better jobs, bank reform (especially to curtail speculative trading by banks), forgiveness of student loan debt or other relief for indebted students, and alleviation of the foreclosure situation. Some media labeled the protests "anti-capitalist," while others disputed the relevance of this label. Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times noted "while alarmists seem to think that the movement is a 'mob' trying to overthrow capitalism, one can make a case that, on the contrary, it highlights the need to restore basic capitalist principles like accountability." Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi asserted, "These people aren't protesting money. They're not protesting banking. They're protesting corruption on Wall Street." In contradiction to such views, academic Slavoj Zizek wrote, "capitalism is now clearly re-emerging as the name of the problem," and Forbes columnist Heather Struck wrote, "In downtown New York, where protests fomented, capitalism is held accountable for the dire conditions that a majority of Americans face amid high unemployment and a credit collapse that has ruined the housing market and tightened lending among banks."

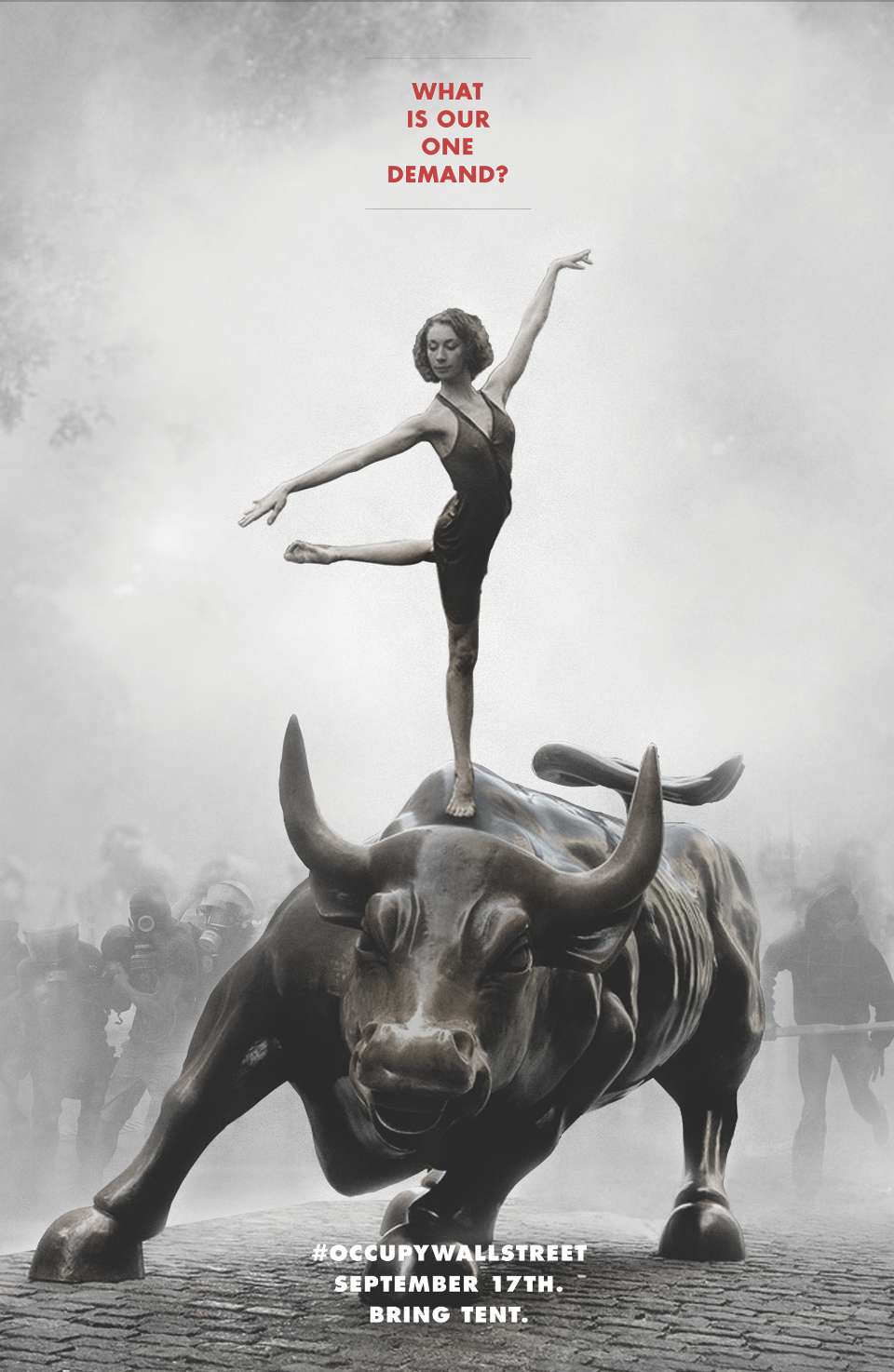

Some protestors favored a fairly concrete set of national policy proposals. One OWS group that favored specific demands created a document entitled the 99 Percent Declaration, but this was regarded as an attempt to "co-opt" the "Occupy" name, and the document and group were rejected by the General Assemblies of Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Philadelphia. However others, such as those who issued the Liberty Square Blueprint, are opposed to setting demands, saying they would limit the movement by implying conditions and limiting the duration of the movement. David Graeber, an OWS participant, also criticized the idea that the movement must have clearly defined demands, arguing that it would be a counterproductive legitimization of the power structures the movement sought to challenge. In a similar vein, scholar and activist Judith Butler challenged the assertion that OWS should make concrete demands: "So what are the demands that all these people are making? Either they say there are no demands and that leaves your critics confused. Or they say that demands for social equality, that demands for economic justice are impossible demands and impossible demands are just not practical. But we disagree. If hope is an impossible demand then we demand the impossible." Regardless, activists favored a new system that fulfills what is perceived as the original promise of democracy to bring power to all the people.

During the occupation in Liberty Square, a declaration was issued with a list of grievances. The declaration stated that the "grievances are not all-inclusive."

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

Funding

During the initial weeks of the park encampment it was reported that most of OWS funding was coming from donors with incomes in the $50,000 to $100,000 range, and the median donation was $22. According to finance group member Pete Dutro, OWS had accumulated over $700,000. The largest single donor to the movement was former New York Mercantile Exchange vice chairman Robert Halper, who was noted by media as having also given the maximum allowable campaign contribution to Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. During the period that protesters were encamped in the park the funds were being used to purchase food and other necessities and to bail out fellow protesters. With the closure of the park to overnight camping on November 15, members of the OWS finance committee stated they would initiate a process to streamline the movement and re-evaluate their budget and eliminate or merge some of the "working groups" they no longer needed on a day-to-day basis.

Met with increasing costs and significant overhead expenses in order to sustain the movement, an internal audit from the fiscal management team known as the "accounting working group" revealed on March 2, 2012, that only $44,000 of the several hundred thousand dollars raised still remained available. The report warned that if current revenues and expenses were maintained at current levels, then funds would run out in three weeks. Some of the movement's biggest costs include ground-level activities such as food kitchens, street medics, bus tickets, subway passes, and printing expenses.

In late February 2012 it was reported that a group of business leaders including Ben Cohen, Jerry Greenfield, Danny Goldberg, Norman Lear, and Terri Gardner created a new working group, the Movement Resource Group, and with it have pledged $300,000 with plans to add $1,500,000 more. The money would be made available in the form of grants of up to $25,000 for eligible recipients.

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

Return to Persagen.com