Google Digital Advertising Antitrust Litigation

| URL |

https://Persagen.com/docs/google-digital_advertising_antitrust_litigation.html |

| Sources |

Persagen.com | other sources (cited in situ) |

| Authors |

Persagen.com |

| Date published |

2021-11-04 |

| Curation date |

2021-11-04 |

| Curator |

Dr. Victoria A. Stuart, Ph.D. |

| Modified |

|

| Editorial practice |

Refer here | Date format: yyyy-mm-dd |

| Summary |

In 2021-10, several states sued Google LLC ("Google") under federal and state antitrust laws and deceptive trade practices laws. |

| Main article |

Google LLC |

| Key points |

|

| Related |

|

|

Show

ENTER_TEXT_HERE

|

| Keywords |

Show

|

| Named entities |

Show

|

| Ontologies |

Show

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Advertising - Online advertising

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Advertising - Online advertising - DoubleClick Inc.

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Advertising - Online advertising - Google LLC

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Advertising - Online advertising - Google LLC - Google Ad Manager

- Culture - Cultural studies - Media culture - Deception - Media manipulation - Advertising - Online advertising - Real-time bidding

- Humanities - Law - Competition law - United States antitrust law

- Society - Business - Corporations - Alphabet Inc. - Subsidiaries - Google LLC

- Society - Business - Corporations - Alphabet Inc. - Subsidiaries - Google LLC - Issues - Legal issues - Antitrust lawsuits

- Society - Issues - Business - Advertising

- Society - Issues - Privacy - Surveillance - Corporate surveillance - Tracking - Advertising ID

- Society - Issues - Privacy - Surveillance - Corporate surveillance - Tracking - Advertising ID - Mobile advertising ID

|

Google Digital Advertising Antitrust Litigation

Complaint (2020-10-20): In the United States District Court for the District of Columbia | local copy (64 pp)

Complaint (2020-10-22): United States District Court Southern District of New York In re: Google Digital Advertising Antitrust Litigation | local copy (173 pp)

The following content is excerpted from the (173 pp.) antitrust lawsuit filed in New York.

The States of Texas, Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Utah, and the Commonwealths of Kentucky and Puerto Rico, by and through their Attorneys General (collectively, the "Plaintiff States"), in the above-styled action, file their Second Amended Complaint ("Complaint") against Google LLC ("Google") under federal and state antitrust laws and deceptive trade practices laws and allege as follows.

I. NATURE OF THE CASE

The halcyon days of Google's youth are a distant memory. Over twenty years ago, two college students founded a company that forever changed the way that people search the internet. Since then, Google has expanded its business far beyond search and dropped its famous "don't be evil" motto. Its business practices reflect that change. As internal Google documents reveal, Google sought to kill competition and has done so through an array of exclusionary tactics, including an unlawful agreement with Facebook, its largest potential competitive threat, to manipulate advertising auctions. The Supreme Court has warned that there are such things as antitrust evils. This litigation will establish that Google is guilty of such antitrust evils, and it seeks to ensure that Google won't be evil anymore.

Google is an advertising company that makes billions of dollars a year by deceptively using individuals' personal information to engage in targeted digital advertising. Google has extended its reach from search advertising to dominate the online advertising landscape for image- based ads on the web, called "display ads." In its complexity, the market for display ads resembles the most complicated financial markets; publishers and advertisers trade display inventory through brokers and on electronic exchanges and networks at lightning speed. As of 2020, Google is a company standing at the apex of power in media and advertising, generating over $161 billion annually with staggering profit margins, almost all from advertising.

Google's advertising apparatus extends to the new ad exchanges and brokers through which display ads trade. Indeed, nearly all of today's online publishers (be they large or small) depend on one company - Google - as their middleman to sell their online display ad space in "ad exchanges," i.e., the centralized electronic trading venues where display ads are bought and sold. Conversely, nearly every consumer goods company, e-commerce entity, and small business now depends on Google as their respective middleman for purchasing display ads from exchanges in order to market their goods and services to consumers. In addition to representing both the buyers and the sellers of online display advertising, Google also operates the largest exchange, AdX. In this electronically traded market, Google is pitcher, batter, and umpire, all at the same time.

The scale of online display advertising markets in the United States is extraordinary. Google operates the largest electronic trading market in existence. Whereas financial exchanges such as the NYSE and NASDAQ match millions of trades to thousands of company symbols daily, Google's exchange processes about 11 billion online ad spaces each day. In Google's words, "hundreds of thousands of publishers and advertisers use Google's AdX exchange to transact inventory, and more daily transactions are made on AdX than on the NYSE and NASDAQ combined." At the same time, Google owns the largest buy-side and sell-side brokers. As one senior Google employee admitted, "the analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE." Or more accurately, the analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank were a monopoly financial broker and owned the NYSE, which was a monopoly stock exchange.

Google, however, did not accrue its monopoly power through excellence in the marketplace or innovations in its services alone. Google's internal documents belie the public image of brainy Google engineers having fun at their sunny Mountain View campus while trying to make the world a better place. Rather, to cement its dominance across online display markets, Google has repeatedly and brazenly violated antitrust and consumer protection laws. Its modus operandi is to monopolize and misrepresent. Google uses its powerful position on every side of online display markets to unlawfully exclude competition. It also deceptively claims that "we'll never sell your personal information to anyone," but its entire business model centers on targeted advertising - the purchase and sale of advertisements targeted to individual users based on their personal information. From its earliest days, Google's carefully curated public reputation of "don't be evil" has enabled it to act with wide latitude. That latitude is enhanced by the extreme opacity and complexity of digital advertising markets, which are at least as complex as the most sophisticated financial markets in the world.

The fundamental change for Google dates back to its 2008 acquisition of DoubleClick, the leading provider of the ad server tools that online publishers, including newspapers and other media companies, use to sell their graphical display advertising inventory on exchanges. After acquiring the leading middleman between publishers and exchanges, Google quickly monopolized the publisher ad server and exchange markets by engaging in unlawful tactics. For instance, Google started requiring publishers to license Google's ad server and to transact through Google's exchange in order to do business with those in another market in which Google possessed monopoly power: the one million plus advertisers who used Google as their middleman for buying inventory. So Google was able to demand that it represent the buy-side (i.e., advertisers), where it extracted one fee, as well as the sell-side (i.e., publishers), where it extracted a second fee, and it was also able to force transactions to clear in its exchange, where it extracted a third, even larger, fee.

Within a few short years of executing this unlawful tactic, Google successfully monopolized the publisher ad server market and grew its ad exchange to number one, despite having entered those two markets much later than the competition. With a newfound hold on publisher ad servers, Google then proceeded to further foreclose publishers' ability to trade in non- Google exchanges. Google imposed a one-exchange-rule on publishers, barring them from routing inventory to more than one exchange at a time. At the same time, Google's ad server blocked competition from non-Google exchanges through a program called Dynamic Allocation and falsely told publishers that Dynamic Allocation maximized their revenue. As internal documents reveal, however, Google's real scheme with Dynamic Allocation was to permit its exchange to snatch publishers' best inventory at the expense of publishers' best interests. One industry publication put it succinctly: "the lack of competition was costing pubs cold hard cash."

In an attempt to reinject competition in the exchange market, a new innovation called header bidding was devised. Publishers could use header bidding to simultaneously route their ad inventory to multiple exchanges in order to solicit the highest bid for the inventory. At first, header bidding promised to bypass Google's stranglehold on the exchange market. By 2016, about 70 percent of major online publishers in the United States had adopted the innovation. Advertisers also migrated to header bidding in droves because it helped them to purchase from exchanges offering the same inventory for the lowest price.

Google quickly realized that this innovation substantially threatened its exchange's ability to demand a very large - 19 to 22 percent - cut on all advertising transactions. Header bidding also undermined Google's ability to trade on inside and non-public information from one side of the market to advantage itself on the other - a practice that in other markets would be considered insider trading or front running. Google deceptively told the public that "we don't see header bidding as a threat to our business. Not at all." But privately, Google's internal communications make clear Google viewed header bidding's promotion of genuine competition as a major threat. In Google's own words, header bidding was an "existential threat."

Google responded to this threat through a series of anticompetitive tactics. First, Google appeared to cede ground and allow publishers using its ad server to route their inventory to more than one exchange at a time. However, Google secretly made its own exchange win, even when another exchange submitted a higher bid. Google's codename for this program was Jedi - a reference to Star Wars. And as one Google employee explained internally, Google deliberately designed Jedi to avoid competition, and Jedi consequently harmed publishers. In Google's words, the Jedi program "generates suboptimal yields for publishers and serious risks of negative media coverage if exposed externally." Next, Google tried to come up with other creative ways to shut out competition from exchanges in header bidding. During one internal debate, a Google employee proposed a "nuclear option" of reducing Google's exchange fees down to zero. A second employee captured Google's ultimate aim of destroying header bidding altogether, noting in response that the problem with simply competing on price is that it "doesn't kill HB (header bidding)." Google wanted to be more aggressive.

Google grew increasingly brazen in its efforts to undermine competition. In March 2017, Google's largest Big Tech rival, Facebook, announced that it would throw its weight behind header bidding. Like Google, Facebook brought millions of advertisers on board to reach the users on its social network. In light of Facebook's deep knowledge of its users, Facebook could use header bidding to operate an electronic marketplace for online ads in competition with Google. Facebook's marketplace for online ads is known as "Facebook Audience Network." Google understood the severity of the threat to its position if Facebook were to enter the market and support header bidding. To diffuse this threat, Google made overtures to Facebook. Internal Facebook communications reveal that Facebook executives fully understood why Google wanted to cut a deal with them: "they want this deal to kill header bidding."

Any collaboration between two competitors of such magnitude should have set off the loudest alarm bells in terms of antitrust compliance. Apparently, it did not. Internally, Google documented that if it could not "avoid competing with Facebook Audience Network," then it wanted to collaborate with Facebook to "build a moat." Indeed, Facebook understood Google's rationale as a monopolist very well. An internal Facebook communication at the highest level reveals that Facebook's header bidding announcement was part of a pre-planned long-term strategy - an "18 month header bidding strategy" - to draw Google in. Facebook decided to dangle the threat of competition in Google's face so it could then cut a deal to manipulate publishers' auctions in its favor.

In the end, Facebook curtailed its involvement with header bidding in return for Google giving Facebook information, speed, and other advantages in the ~43 billion auctions Google runs for publishers' mobile app advertising inventory each month in the United States. As part of this agreement, Google and Facebook work together to identify users using Apple products. The parties also agreed up front on quotas for how often Facebook would win publishers' auctions - literally manipulating the auction with minimum spends and quotas for how often Facebook would bid and win. In these auctions, Facebook and Google compete head-to-head as bidders. Google's internal codename for this agreement, signed at the highest-level, was Jedi Blue - a twist on the Star Wars reference.

Above and beyond its unlawful agreement with Facebook, Google employed a number of other anticompetitive tactics to shut down competition from header bidding. Google deceived non-Google exchanges into bidding through Google instead of header bidding, telling them it would stop front running their orders when in fact it would not. Google employees also deceived publishers, telling one major online publisher that it should cut off a rival exchange in header bidding because of a strain on its servers. After this misrepresentation was uncovered, Google employees discussed playing a trick - a "Jedi mind trick" - on the industry to nonetheless get publishers to cut off exchanges in header bidding. Google wanted to "get publishers to come up with the idea to remove exchanges ... on their own." Google then proceeded to cripple publishers' ability to use header bidding in a variety of ways.

Having reached its monopoly position, Google now uses its immense market power to extract a very high tax of 22 to 42 percent of the ad dollars otherwise flowing to the countless online publishers and content producers such as online newspapers, cooking websites, and blogs who survive by selling advertisements on their websites and apps. These costs invariably are passed on to the advertisers themselves and then to American consumers. The monopoly tax Google imposes on American businesses - advertisers like clothing brands, restaurants, and realtors - is a tax that is ultimately borne by American consumers through higher prices and lower quality on the goods, services, and information those businesses provide. Every American suffers when Google imposes its monopoly pricing on the sale of targeted advertising.

From its earliest days, the internet's fundamental tenet has been its decentralization: there is no controlling node, no single point of failure, and no central authority granting permission to offer or access online content. Online advertising is uniquely positioned to provide content to users at a massive scale. However, the open internet is now threatened by a single company. Google has become the controlling node and the central authority for online advertising, which serves as the primary currency enabling a free and open internet.

Google's current dominance is also merely a preview of its future plans. Google's latest announcements with respect to its Chrome browser and privacy will further its longstanding plan to create a "walled garden" - a closed ecosystem - out of the otherwise-open internet. At the same time, Google uses "privacy" as a pretext to conceal its true motives.

In sum, Google's anticompetitive conduct has adversely and substantially affected the Plaintiff States' economies, as well as the general welfare in the Plaintiff States. Google's illegal conduct has reduced competition, raised prices, reduced quality, and reduced output in each of the Plaintiff States. This conduct has harmed the Plaintiff States' respective economies by depriving the Plaintiff States and the persons within each Plaintiff State of the benefits of competition.

As a result of Google's deceptive trade practices and anticompetitive conduct, including its unlawful agreement with Facebook, Google has violated and continues to violate Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1, 2, as well as state antitrust and consumer protections laws. Plaintiff States bring this action to remove the veil of Google's secret practices and put an end to Google's anticompetitive abuses of its monopoly power in online advertising markets. Plaintiff States seek to restore free and fair competition to these markets and to secure structural, behavioral, and monetary relief to prevent Google from ever again engaging in deceptive trade practices and abusing its monopoly power to foreclose competition and harm consumers.

II. PARTIES

[ ... snip ... ]

Google Project NERA

[Twitter.com, 2021-10-23] Twitter.com/fasterthanlime/status/1452053941504684036: Google had a plan called "Project NERA" to turn the web into a walled garden they called "Not Owned But Operated." A core component of this was the forced logins to the chrome browser you've probably experienced (surprise!) | Discussion, Hacker News: 2021-10-24

Google-Facebook Antitrust Collusion: "Jedi Blue"

Accelerated Mobile Pages [AMP]

Related: Accelerated Mobile Pages (text below sourced 2021-10-24).

AMP (originally an acronym for Accelerated Mobile Pages) is an open source HTML framework developed by the AMP Open Source Project. It was originally created by Google as a competitor to Facebook Instant Articles and Apple News. AMP is optimized for mobile web browsing and intended to help webpages load faster. AMP pages may be cached by a CDN, such as Microsoft Bing or Cloudflare's AMP caches, which allows pages to be served more quickly.

AMP was first announced on October 7, 2015. After a technical preview period, AMP pages began appearing in Google mobile search results in February 2016. AMP has been criticized for potentially giving further control over the web to Google and other concerns. The AMP Project announced it would move to an open governance model on September 18, 2018.

[WPTavern.com, 2021-11-05] AMP Has Irreparably Damaged Publishers' Trust in Google-led Initiatives. | local copy | Discussion: Hacker News: 2021-11-06

The Chrome Dev Summit 2021 concluded earlier this week [first week of 2021-11]. Announcements and discussions on hot topics impacting the greater web community at the event included Google's Privacy Sandbox initiative, improvements to Core Web Vitals and performance tools, and new APIs for Progressive Web Apps (PWAs). Paul Kinlan, Lead for Chrome Developer Relations, highlighted the latest product updates on the Chromium blog, what he identified as Google's "vision for the web's future and examples of best-in-class web experiences."

During an (AMA) live Q&A session with Chrome Leadership, ex-AMP Advisory Board member Jeremy Keith asked a question that echoes the sentiments of developers and publishers all over the world who are viewing Google's leadership and initiatives with more skepticism.

Given the court proceedings against AMP, why should anyone trust FLoC or any other Google initiatives ostensibly focused on privacy?

The question drew a tepid response from Chrome leadership who avoided giving a straight answer. Ben Galbraith fielded the question, saying he could not comment on the AMP-related legal proceedings but focused on the Privacy Sandbox.

I think it's important to note that we're not asking for blind trust with the Sandbox effort. Instead, we're working in the open, which means that we're sharing our ideas while they are in an early phase. We're sharing specific API proposals, and then we're sharing our code out in the open and running experiments in the open. In this process we're also working really closely with industry regulators. You may have seen the agreement that we announced earlier this year jointly with the UK's CMA, and we have a bunch of industry collaborators with us. We'll continue to be very transparent moving forward, both in terms of how the Sandbox works and its resulting privacy properties. We expect the effort will be judged on that basis.

FLoC continues to be a controversial initiative, opposed by many major tech organizations. A group of like-minded WordPress contributors proposed blocking Google's initiative earlier this year. Privacy advocates do not believe FLoC to be a compelling alternative to the surveillance business model currently used by the advertising industry. Instead, they see it as an invitation to cede more control of ad tech to Google.

Galbraith's statement conflicts with the company's actions earlier this year when Google said the team does not intend to disclose any of the private feedback received during FLoC's origin trial, which was criticized as a lack of transparency.

Despite the developer community's waning trust in the company, Google continues to aggressively advocate for a number of controversial initiatives, even after some of them have landed the company in legal trouble. Google employees are not permitted to talk about the antitrust lawsuit and seem eager to distance themselves from the proceedings.

Jeremy Keith's question referencing the AMP allegations in the recently unredacted antitrust complaint [local copy] against Google was extremely unlikely to receive an adequate response from the Chrome Leadership team, but the mere act of asking is a public reminder of the trust Google has willfully eroded in pushing AMP on publishers.

When Google received a demand for a trove of documents from the Department of Justice as part of the pre-trial process, the company was reluctant to hand them over. These documents reveal how Google identified header bidding as an "existential threat" and detail how AMP was used as a tool to impede header bidding.

The complaint alleges that "Google ad server employees met with AMP employees to strategize about using AMP to impede header bidding, addressing in particular how much pressure publishers and advertisers would tolerate."

In summary, it claims that Google falsely told publishers that adopting AMP would enhance load times, even though the company's employees knew that it only improved the "median of performance" and actually loaded slower than some speed optimization techniques publishers had been using. It alleges that AMP pages brought 40% less revenue to publishers. The complaint states that AMP's speed benefits "were also at least partly a result of Google's throttling. Google throttles the load time of non-AMP ads by giving them artificial one-second delays in order to give Google AMP a 'nice comparative boost.'"

Although the internal documents were not published alongside the unredacted complaint, these are heavy claims for the Department of Justice to float against Google if the documents didn't fully substantiate them.

The AMP-related allegations are egregious and demand a truly transparent answer. We all watched as Google used its weight to force publishers both small and large to adopt its framework or forego mobile traffic and placement in the Top Stories carousel. This came at an enormous cost to publishers who were unwilling to adopt AMP.

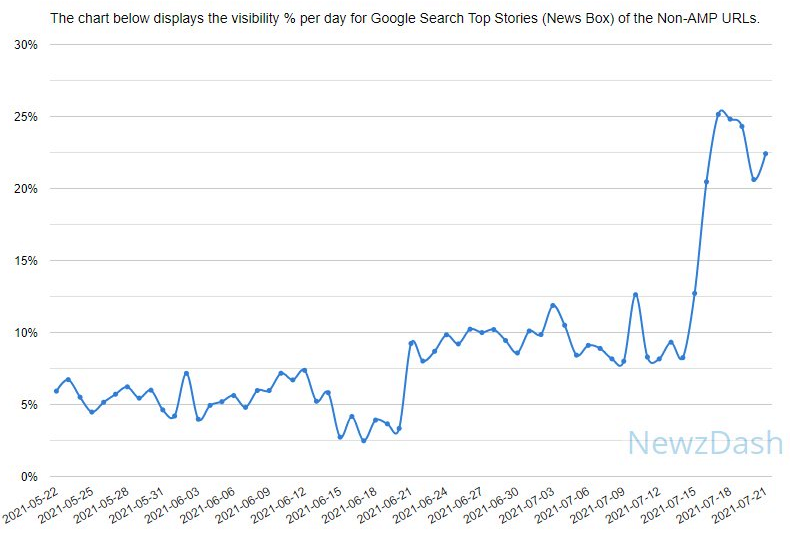

Barry Adams, one of the most vocal critics of the AMP project, demonstrated this cost to publishers in a graph that shows the percentage of articles in Google's mobile Top Stories carousel in the US that are not AMP articles. When Google stopped requiring AMP for the mobile Top Stories in July 2021, there was a sharp spike in non-AMP URLs being included.

Once AMP was no longer required and publishers could use any technology to rank in Top Stories, the percentage of non-AMP pages increased significantly to double digits, where it remains today. Adams' article calls on the web community to recognize the damage Google did in giving AMP pages preferential treatment.

"But I'm angry. Because it means that for more than five long years, when AMP was a mobile Top Stories requirement, Google penalised these publishers for not using AMP.

"There was no other reason for Google to stop ranking these publishers in their mobile Top Stories carousel. As is evident from the surge of non-AMP articles, there are likely hundreds - if not thousands - of publishers who ticked every single ranking box that Google demanded; quality news content, easily crawlable and indexable technology stack, good editorial authority signals, and so on.

"But they didn't use AMP. So Google didn't rank them. Think for a moment about the cost of that."

Even the publishers who adopted AMP struggled to get ad views. In 2017, Digiday reported on how many publishers have experienced decreased revenues associated with ads loading much slower than the actual content. I don't think anyone at the time imagined that Google was throttling the non-AMP ads. "The aim of AMP is to load content first and ads second," a Google spokesperson told Digiday. "But we are working on making ads faster. It takes quite a bit of the ecosystem to get on board with the notion that speed is important for ads, just as it is for content."

This is why Google is rapidly losing publishers' trust. For years the company encumbered already struggling news organizations with the requirement of AMP. The DOJ's detailed description of how AMP was used as a vehicle for anticompetitive practices simply rubs salt in the wound after what publishers have been through in expending resources to support AMP versions of their websites.

Automattic Denies Prior Knowledge of Google Throttling Non-AMP Ads

In 2016, Automattic, one of the most influential companies in the WordPress ecosystem, partnered with Google to promote AMP as an early adopter. WordPress.com added AMP support and Automattic built the first versions of the AMP plugin for self-hosted WordPress sites. The company has played a significant role in driving AMP adoption forward, giving it an entrance into the WordPress ecosystem.

How much did Automattic know when it partnered with Google in the initial AMP rollout? I asked the company what the precise nature of its relationship with Google is regarding AMP at this time.

[ ... snip ... ]

The antitrust complaint also details a Project NERA, which was designed to "successfully mimic a walled garden across the open web." When asked about this, Automattic reiterated its commitment to supporting the open web and gave the same response: "We were not aware of any actions that did not align with our company's mission."

[ ... snip ... ]

Federated Learning of Cohorts

Related: Federated Learning of Cohorts (text below sourced 2021-10-24).

Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC) is a type of web tracking through federated learning. It groups people into "cohorts" based on their browsing history for the purpose of interest-based advertising. Google began testing the technology in the Chrome browser in March 2021 as a replacement for third-party cookies, which it plans to stop supporting in Chrome by early 2023. FLoC is being developed as a part of Google's Privacy Sandbox initiative, which includes several other advertising-related technologies with bird-themed names.

As of April 2021, every major browser aside from Google Chrome that is based on Google's open-source Chromium platform has declined to implement FLoC. The technology has been criticized on privacy grounds by groups including the Electronic Frontier Foundation and DuckDuckGo, and has been described as anti-competitive; it has generated an antitrust response in multiple countries as well as questions about General Data Protection Regulation compliance.

Project Bernanke

In April 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that Google ran a years-long program called 'Project Bernanke' that used data from past advertising bids to gain an advantage over competing for ad services. This was revealed in documents concerning the antitrust lawsuit filed by ten US states against Google in December 2020. [Source: Wikipedia, 2021-11-14.]

[WSJ.com, 2021-04-11] Google's Secret 'Project Bernanke' Revealed in Texas Antitrust Case. Program used past bid data to boost tech company's win rate in advertising auctions, according to court filing. Archive.today snapshot | local copy

Google for years operated a secret program that used data from past bids in the company's digital advertising exchange to allegedly give its own ad-buying system an advantage over competitors, according to court documents filed in a Texas antitrust lawsuit.

The program, known as "Project Bernanke," wasn't disclosed to publishers who sold ads through Google's ad-buying systems. It generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the company annually, the documents show. In its lawsuit, Texas alleges that the project gave Google, a unit of Alphabet Inc., an unfair competitive advantage over rivals.

The documents filed this week were part of Google's initial response to the Texas-led antitrust lawsuit, which was filed in December and accused the search giant of running a digital-ad monopoly that harmed both ad-industry competitors and publishers. This week's filing, viewed by The Wall Street Journal, wasn't properly redacted when uploaded to the court's public docket. A federal judge let Google refile it under seal.

Some of the unredacted contents of the document were previously disclosed by MLex [LexisNexis], an antitrust-focused news outlet.

[ ... snip ... ]

[theVerge.com, 2021-04-11] Google reportedly ran secret 'Project Bernanke' that boosted its own ad-buying system over competitors. The information was revealed in unredacted court documents.

Google reportedly ran a secret project called "Project Bernanke" that relied on bidding data collected from advertisers using its ad exchange to benefit the company's own ad system, The Wall Street Journal reported. First discovered by newswire service MLex [LexisNexis], the name of the project was visible in an inadvertently unredacted document Google had filed as part of an antitrust lawsuit in Texas.

A federal judge has since let Google refile the document under seal. But according to the Journal, "Bernanke" was not disclosed to outside advertisers, and proved lucrative for Google, generating hundreds of millions of dollars for the company. Texas filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google in December 2020, alleging that the search giant was using anticompetitive tactics in which "Bernanke" was a major part.

Google wrote in the unredacted filing that data from Project Bernanke was "comparable to data maintained by other buying tools," according to The Wall Street Journal. The company was able to access historical data about bids made through Google Ads, to change bids by its clients and boost the clients' chances of winning auctions for ad impressions, putting rival ad tools at a disadvantage. Texas cited in court documents an internal presentation from 2013 in which Google said Project Bernanke would bring in $230 million in revenue for that year.

Why Google chose to name the secret project "Bernanke" is not clear. Ben Bernanke, who was Chair of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014, is probably the best-known Bernanke in the public sphere.

In an email to The Verge, a Google spokesperson said the complaint by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton "misrepresents many aspects of our ad tech business. We look forward to making our case in court."

Additional Reading: Google Digital Advertising Antitrust Litigation

[theRegister.com, 2021-10-22] Antitrust battle latest: Google, Facebook 'colluded' to smash Apple's privacy protections. Amended Texas complaint alleges backroom efforts to maintain ad dominance and more. | We have been successful in slowing down and delaying the [European ePrivacy Regulation] process and have been working behind the scenes hand in hand with the other companies. | Google secretly made its own exchange win, even when another exchange submitted a higher bid. | Discussion, Hacker News: 2021-10-23

Several years ago, to deal with the competitive threat of header bidding - a way for multiple ad exchanges to get a fair shot at winning an automated auction for ad space - Google allegedly hatched a plan called "Jedi" [ disambiguation: not Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI)]to ensure that its ad exchange always won. And in 2017, after Facebook announced plans to support header bidding, Google, it's claimed, struck a deal with Facebook - dubbed "Jedi Blue" - in which the two internet behemoths would "work together to identify users using Apple products," and set up "quotas for how often Facebook would win publishers' auctions." The Jedi project is described in an amended complaint [pdf | local copy; discussion, Hacker News: 2021-10-24], filed Friday [2021-10-22], that expands the December 2020 antitrust claim against Google, brought by Texas, 14 other US states, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

The Texas antitrust case against Google is one of four ongoing government-backed claims in the US alleging the web search giant competes unfairly. A year ago, the US Justice Department filed a federal antitrust lawsuit. Colorado also filed a complaint last December [2020] on behalf of a group of 38 states. Then there's the complaint filed in July [2021] over Android and the Google Play Store, backed by 36 US states and commonwealths, along with Washington DC.

The amended complaint in the Texas litigation expands on a claim in the initial complaint about Google's alleged effort to delay privacy legislation, with help from Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft, at a closed-door meeting between the corporations on August 6, 2019. To make the case that Google's publicly stated concern about privacy is a sham, the new text describes a Google document prepared in advance of the meeting that said, "we have been successful in slowing down and delaying the [ePrivacy Regulation] process and have been working behind the scenes hand in hand with the other companies," referring to the European Commission's data protection rules.

Header bidding emerged around 2015 as a way to bypass Google's control of the ad auction ecosystem and the fees it charged. By 2016, the court filing explains, about 70 per cent of major publishers were using header bidding to offer their ad space to multiple ad exchanges at the same time, not just Google, to get the best deal from advertisers. "Google quickly realized that this innovation substantially threatened its exchange's ability to demand a very large - 19 to 22 percent - cut on all advertising transactions," the revised complaint says. "Header bidding also undermined Google's ability to trade on inside and non-public information from one side of the market to advantage itself on the other - a practice that in other markets would be considered insider trading or front running."

[ ... snip ... ]

[WSJ.com, 2021-10-20] Justice Department Hits Google With Antitrust Lawsuit. Suit follows lengthy investigation into company's dominance of search traffic and effect on competition.

[Forbes.com, 2021-01-19] Jedi Blue: A Scandal That Highlights, Yet Again, The Need To Regulate Big Tech. The Jedi Blue case, exposed by The Wall Street Journal and followed up on [source] by The New York Times, is a clear example of the abuse of Google and Facebook's dominant positions, and definitive proof as to why the tech giants need regulating. It's pretty much a textbook case of everything that can go wrong an industry. What is Jedi Blue? Basically a quid-pro-quo scheme that starts with Google's 2007 acquisition of DoubleClick, and ends with Facebook, in 2018, agreeing not to challenge Google's advertising business in return for a very special treatment in Google's ad auctions. ...

[WSJ.com, 2020-10-20] Justice Department Hits Google With Antitrust Lawsuit. Suit follows lengthy investigation into company's dominance of search traffic and effect on competition. | Archive.today snapshots | local copy

The Justice Department filed a long-expected antitrust lawsuit [local copy] alleging that Google uses anticompetitive tactics to preserve a monopoly for its flagship search engine and related advertising business, the most aggressive U.S. legal challenge to a company's dominance in the tech sector in more than two decades. The case, filed Tuesday [2020-10-19] in federal court in Washington, D.C., alleged that the Alphabet Inc. unit [Google LLC] maintains its status as gatekeeper to the internet through an unlawful web of exclusionary and interlocking business agreements that shut out competitors.

The government alleged that Google uses billions of dollars collected from advertisements on its platform to pay for mobile-phone manufacturers, carriers and browsers, like Alphabet Inc.'s Safari web browser, to maintain Google as their preset, default search engine, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of dominance.

The upshot is that Google has pole position in search on hundreds of millions of devices in the U.S., with little opportunity for any other company to make inroads, the government said.

[ ... snip ... ]

[NYTimes.com, 2021-01-17] Behind a Secret Deal Between Google and Facebook. Facebook was going to compete with Google for some advertising sales but backed away from the plan after the companies cut a preferential deal, according to court documents. | Mentions: antitrust lawsuit; Jedi Blue; header bidding; ...

This is a draft article [additional content pending ...].

[ ... snip ... ]

Additional Reading

[Reuters.com, 2021-11-13] U.S. states file updated antitrust complaint against Alphabet's Google. | Discussion: Hacker News: 2021-11-14

A group of U.S. states led by Texas have filed an amended complaint against Alphabet Inc.'s Google accusing the tech giant of using coercive tactics and breaking antitrust laws in its efforts to boost its already dominant advertising business. The updated allegations are the latest in an onslaught of regulatory scrutiny of Google over its practices. The tech company faces several lawsuits, including one by the Justice Department for monopolistic practices. Earlier this week [2021-11], Google lost an appeal against a $2.8 billion European Union antitrust decision.

The amended U.S. lawsuit, filed in a federal court in New York late Friday [2021-11-12], accuses Google of using monopolistic and coercive tactics with advertisers in its efforts to dominate and drive out competition in online advertising

.

The lawsuit also highlights Google's use of a secret program dubbed "Project Bernanke" in 2013 that used bidding data to give its own ad-buying an advantage. For example, in a 2015 iteration of the program, Google allegedly dropped the second-highest bids from publishers' auctions, accumulated money into a pool and then spent that money to inflate only the bids belonging advertisers who used the company's Google Ads. They otherwise would have likely lost the auctions, the states alleged

.

Neither Alphabet nor the Texas Attorney General's office responded immediately to requests for comment on the lawsuit.

Return to Persagen.com