Inflation

| URL |

https://Persagen.com/docs/ |

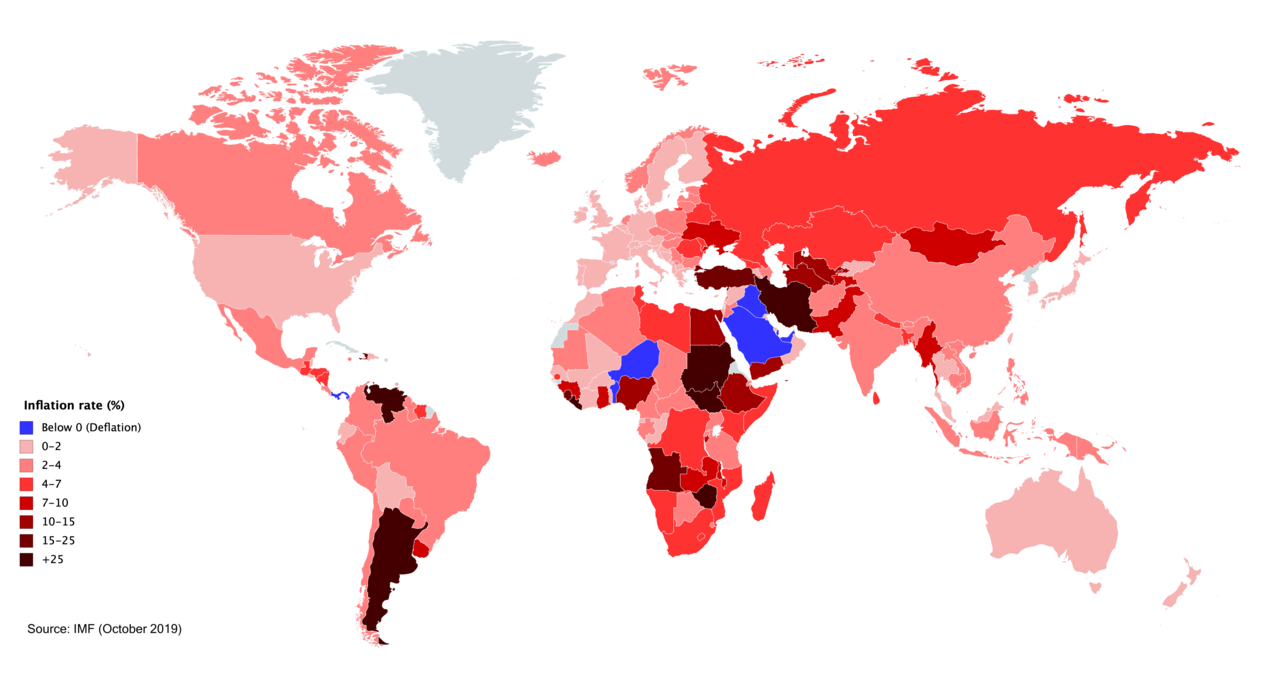

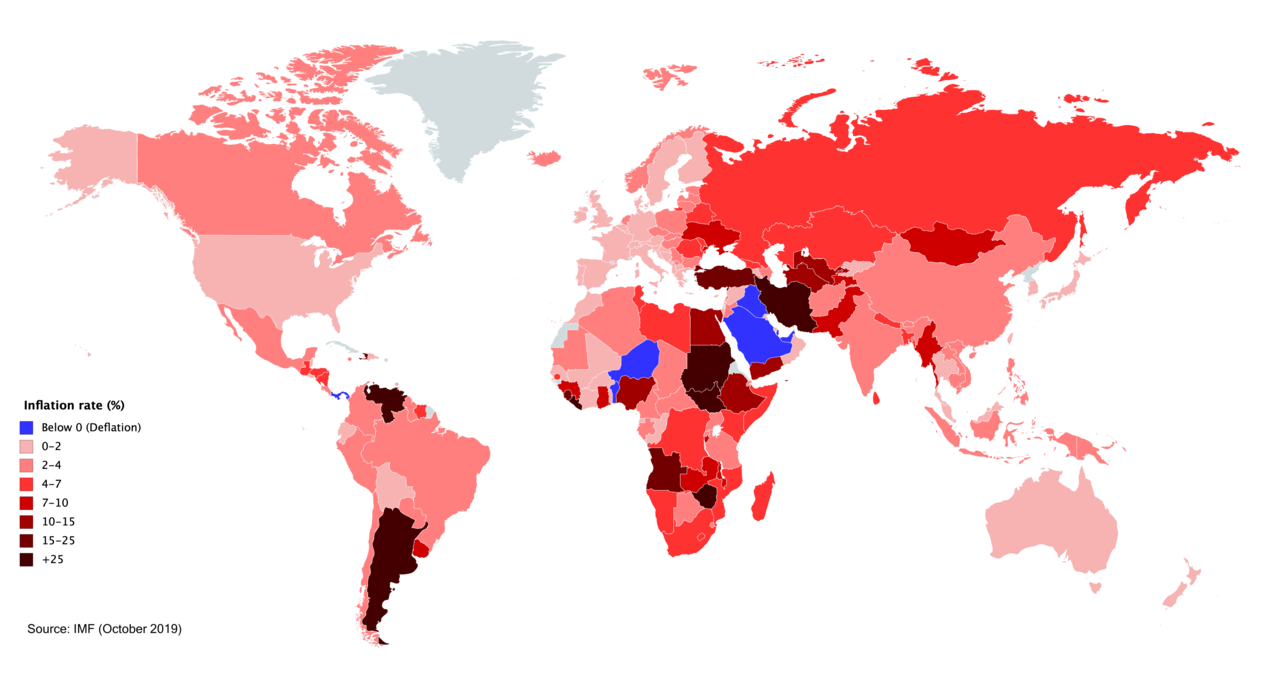

Inflation in countries around the world in 2019.

|

| Sources |

Persagen.com | Wikipedia | other sources (cited in situ) |

| Source URL |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inflation |

| Date published |

2021-11-15 |

| Curation date |

2021-11-15 |

| Curator |

Dr. Victoria A. Stuart, Ph.D. |

| Modified |

|

| Editorial practice |

Refer here | Date format: yyyy-mm-dd |

| Summary |

In economics, inflation refers to a general progressive increase in prices of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduction in the purchasing power of money. The opposite of inflation is deflation, a sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services. The common measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualised percentage change in a general price index. |

| Key points |

|

| Related |

|

|

Show

Comment pieces and policy papers by right-wing think tanks such as the Fraser Institute perpetuate neoliberal agendae and influence policymakers. Two recent articles by persons closely affiliated with the Fraser Institute argue that higher consumer prices during the COVID-19 pandemic are "good" for Canadians and the economy.

|

| Keywords |

Show

|

| Named entities |

Show

|

| Ontologies |

Show

- Society - Charitable giving & Practices - Politics - Countries - Canada - Organizations - Nonprofit organizations - Fraser Institute

- Science - Social sciences - Economics - Inflation

- Science - Social sciences - Economics - Economic systems - Capitalism

- Science - Social sciences - Economics - Economic systems - Capitalism - Competition - Monopolies

- Science - Social sciences - Economics - Economic systems - Capitalism - Ideology - Economic liberalism

- Science - Social sciences - Economics - Economic systems - Capitalism - Ideology - Neoliberalism

- Society - Business - Corporations

- Society - Issues - Business - Neoliberalism

- Society - Business - Management - Business administration - Corporate law - Corporate crime - Profiteering

- Society - Business - Management - Business administration - Corporate law - Corporate crime - Profiteering - Pandemic Profiteering

|

Background

In economics, inflation refers to a general progressive increase in prices of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduction in the purchasing power of money. The opposite of inflation is deflation, a sustained decrease in the general price level of goods and services. The common measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualised percentage change in a general price index.

Prices will not all increase at the same rates. Attaching a representative value to a set of prices is an instance of the index number problem. The consumer price index is often used for this purpose; the employment cost index is used for wages in America. Differential movement between consumer prices and wages constitutes a change in the standard of living.

The causes of inflation have been much discussed, the consensus being that growth in the money supply is usually responsible.

If money was perfectly neutral, inflation would have no effect on the real economy; but perfect neutrality is not generally considered believable. Effects on the real economy are severely disruptive in the cases of very high inflation and hyperinflation. More moderate inflation affects economies in both positive and negative ways. The negative effects include an increase in the opportunity cost of holding money, uncertainty over future inflation which may discourage investment and savings, and if inflation were rapid enough, shortages of goods as consumers begin hoarding out of concern that prices will increase in the future. Positive effects include reducing unemployment due to nominal wage rigidity, allowing the central bank greater freedom in carrying out monetary policy, encouraging loans and investment instead of money hoarding, and avoiding the inefficiencies associated with deflation.

Today, most economists favour a low and steady rate of inflation. Low (as opposed to zero or negative) inflation reduces the severity of economic recessions by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly in a downturn, and reduces the risk that a liquidity trap prevents monetary policy from stabilising the economy. The task of keeping the rate of inflation low and stable is usually given to monetary authorities. Generally, these monetary authorities are the central banks that control monetary policy through the setting of interest rates, by carrying out open market operations and (more rarely) changing commercial bank reserve requirements.

[ ... snip ... ]

This is a draft article [additional content pending]..

Please see Wikipedia for the continuation of this content ...

Inflation: Opposing Views

Inflation Is Good For You

[Jon Schwarz [Twitter], theIntercept.com, 2021-11-10] Inflation Is Good for You. Don't panic over milk prices. Inflation is bad for the 1 percent but helps out almost everyone else. | A panic about inflation usefully creates the conditions to weaken the power of working people.

The top story on The New York Times website this morning is about inflation, and it's scary: "Inflation spiked in October, sinking Washington's hopes that price gains would slow down." The Washington Post led with a similar call for alarm: "Prices climbed 6.2 percent in October compared to last year, the largest increase in 30 years, as inflation strains economy."

... And what's happening is this: The inflation freakout is all about class conflict. In fact, it may be the fundamental class conflict: that between creditors and debtors, a fight that's been going on since the foundation of the United States. That's because inflation is often good for most of us, but it's terrible for the kinds of people who own corporate news outlets - or, say, founded coal firms. And a panic about inflation usefully creates the conditions to weaken the power of working people.

... First, inflation lessens the real value of debt. ... Second, inflation generally accompanies economic booms, when the unemployment rate is low and workers have the market power to demand higher pay. ...

... Put these two things together - lowered values for their assets and higher wages for workers - and you can understand why the rich people who run the U.S. absolutely detest inflation.

However, there is one rock that can kill both these birds at the same time. The Federal Reserve can raise interest rates. This would slow the economy and increase the unemployment rate, lessening worker bargaining power. Less bargaining power would mean lower or nonexistent raises, which would eventually translate into lower inflation.

That's what all today's inflation panic is ultimately aimed at: creating an economy with higher unemployment, lower growth, and more frightened workers. Whether America's creditors can make this happen remains to be seen, but we shouldn't have any illusions about what they're trying to do. And we definitely shouldn't help them do it.

Inflation Is Good For You: Fraser Institute

The Fraser Institute is a Canadian public policy think tank and registered charity. The Fraser Institute has been described as politically conservative and libertarian. The Fraser Institute describes itself as "an independent international research and educational organization", and envisions "a free and prosperous world where individuals benefit from greater choice, competitive markets, and personal responsibility".

The Fraser Institute has received donations of hundreds of thousands of dollars from foundations controlled by Charles Koch and David Koch, with total donations estimated to be approximately $765,000 from 2006 to 2016. The Fraser Institute also received US$120,000 from ExxonMobil in the 2003 to 2004 fiscal period. In 2016, it received a $5 million donation from Peter Munk, a Canadian businessman.

In 2012, The Vancouver Observer [now: National Observer] reported that the Fraser Institute had "received over $4.3 million in the last decade from eight major American foundations including the most powerful players in oil and pharmaceuticals". According to the article, "The Fraser Institute received $1.7 million from 'sources outside Canada' in one year alone, according to the group's 2010 Canada Revenue Agency return. Fraser Institute President Niels Veldhuis [local copy] told The Vancouver Observer that the Fraser Institute does accept foreign funding, but he declined to comment on any specific donors or details about the donations."

Given that Libertarian / neoliberal background, it is not surprising that the Fraser Institute and it's members favorably regard inflation as a positive economic force. That stance is reflected in several recent articles, authored by Fraser Institute members or alumni.

[FinancialPost.com, 2021-11-10] Opinion: What's causing inflation? Bottlenecks or too much money? | local copy While that article does not mention Herbert Grubel's affiliation with the Fraser Institute, Grubel's Wikipedia page states [2021-11-16] "... As of 2011 he is professor emeritus of economics at Simon Fraser University and senior fellow of the Fraser Institute. ..." As of 2021-11-16, Herbert Grubel still has a biography page [local copy, 2021-11-16] at the Fraser Institute.

[Steven Horwitz, Fraser Institute, 2020-03-27] Price Controls and Anti-gouging Laws Make Matters Worse. | That Fraser Institute blog post provides an exemplar of neoliberal ideology.

[North99.org, 2020-04-09] Fraser Institute defends price-gouging amidst COVID-19 pandemic. | while North99.org content is usually excluded from Persagen.com, the cited article is innocuous and provides context.

Inflation Is Bad For You

[Robert Reich, RobertReich.org, 2021-11-10] What's Really Driving Inflation? Corporate Power.

The biggest culprit for rising prices that's not being talked about is the increasing economic concentration of the American economy in the hands of a relative few giant big corporations with the power to raise prices. If markets were competitive, companies would seek to keep their prices down in order to maintain customer loyalty and demand. When the prices of their supplies rose, they'd cut their profits before they raised prices to their customers, for fear that otherwise a competitor would grab those customers away.

But strange enough, this isn't happening. In fact, even in the face of supply constraints, corporations are raking in record profits. More than 80 percent of big (S&P 500) companies that have reported results this season have topped analysts' earnings forecasts, according to Refinitiv.

... The underlying structural problem isn't that government is over-stimulating the economy. It's that big corporations are under competitive. Corporations are using the excuse of inflation to raise prices and make fatter profits. The result is a transfer of wealth from consumers to corporate executives and major investors.

This has nothing to do with inflation, folks. It has everything to do with the concentration of market power in a relatively few hands. It's called "oligopoly," meaning that two or three companies roughly coordinate their prices and output.

... Industry experts say oil and gas companies (and their CEOs and major investors) saw bigger money in letting prices run higher before producing more supply. They can get away with this because big oil and gas producers don't face much competition. They're powerful oligopolies. Again, inflation isn't driving most of these price increases. Corporate power is driving them.

Inflation: Good or Bad?

[CBC.ca, 2021-11-15] Will inflation be a horror or a healthy readjustment? Economists clash over the basics. Why is this happening, how long will it last, is it good or bad? It depends who you ask

What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, but as Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem recently remarked, the same thing does not apply to what happens in financial markets. "It has real impacts," Macklem told the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations [Wikipedia entry] in October 2021. And this week, some newly released data from that very month is likely to prove him right.

On the heels of U.S. inflation figures that last week shocked politicians and unsettled markets, Canada will get its own October 2021 reading on rising prices on Wednesday [2021-11-17].

From Nero to Newton

For a phenomenon observed in Nero's Rome and studied by some of humanity's best minds, including Sir Isaac Newton - who besides transforming physics with his laws of motion battled inflation as Master of the Mint - modern scholars remain surprisingly divided on the subject.

If history is any guide, periods of inflation can lead to turmoil. This week, financial markets will be waiting anxiously to see how close Canada's inflation rate comes to the U.S. gain of 6.2 per cent.

But even if price increases reach only five per cent by year's end - a number suggested by Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem himself at the last monetary policy news conference at the end of October 2021 - price changes at those levels could have an increasingly negative effect on the lives of Canadians.

Those effects include the pain of shrinking spending power, the prospect of labour conflict as employees struggle to get their spending power back, a potential disruption of Canada's soaring housing market and a reconsideration for older people about how to make their money last through a long retirement.

Just as in the United States, where opponents of President Joe Biden are using inflation to attack government policy, some Canadian critics say rising inflation will have negative consequences for Canada's governing Liberals.

Of course, that depends on whether you think the current bout of inflation is good or bad, what has caused it, what the remedies might be and how long it will last. Canadians who imagine economics as a discipline with clear rules and definitive outcomes may be surprised to find that all of those things remain in dispute.

Inflation Good or Inflation Bad?

Last week, commentator Jon Schwarz - [writing in The Intercept - offered a take on the economic argument for why inflation is good - a sort of natural repair mechanism for an economy out of whackl "Inflation is bad for the 1 per cent but helps out almost everyone else," says the headline at the top of Schwarz's story.

The nub of the argument is that for people who have big loans, inflation makes them smaller in dollar terms. As wages and prices inflate, loans can be paid off in inflated dollars. For lenders or people with piles of cash, the effect is the opposite.

It is clear that those saving for retirement may take a different view, especially as the baby boomer bulge exits the labour market. Even before the latest round of COVID-19 pandemic monetary stimulus, people contemplating a long retirement complained about a paltry return on savings. With inflation higher than the rate of interest, cautious savers are now watching with horror as their future spending power shrinks.

And that disparity is not just on the side of savers. As Hilliard MacBeth, an Edmonton-based financial adviser and author of When the Bubble Bursts, observed, even before the latest U.S. inflation surprise, lenders have been handing out mortgages at rates considerably less than the rate of inflation.

"Even three per cent makes no sense in a 5.4 per cent [consumer price index] world," Hilliard MacBeth tweeted.

But as he points out, that depends on whether you think inflation is settling in for the long term or, as central bankers have long insisted, it is a short-term, "transitory" effect caused by events tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mortgage Loans Boost Money Supply

University of British Columbia economist Michael Devereux believes one-time impacts, such as the shipping bottleneck, are the main forces driving rising prices. But like others, he is not sure the inflationary effect will disappear once Canadians grow to expect it. People may keep demanding higher wages and businesses higher prices as they try to catch up with inflation.

Another strong contender for inflation's cause - a flood of new money into the economy caused by the central banks themselves - has led to heated arguments among economists.

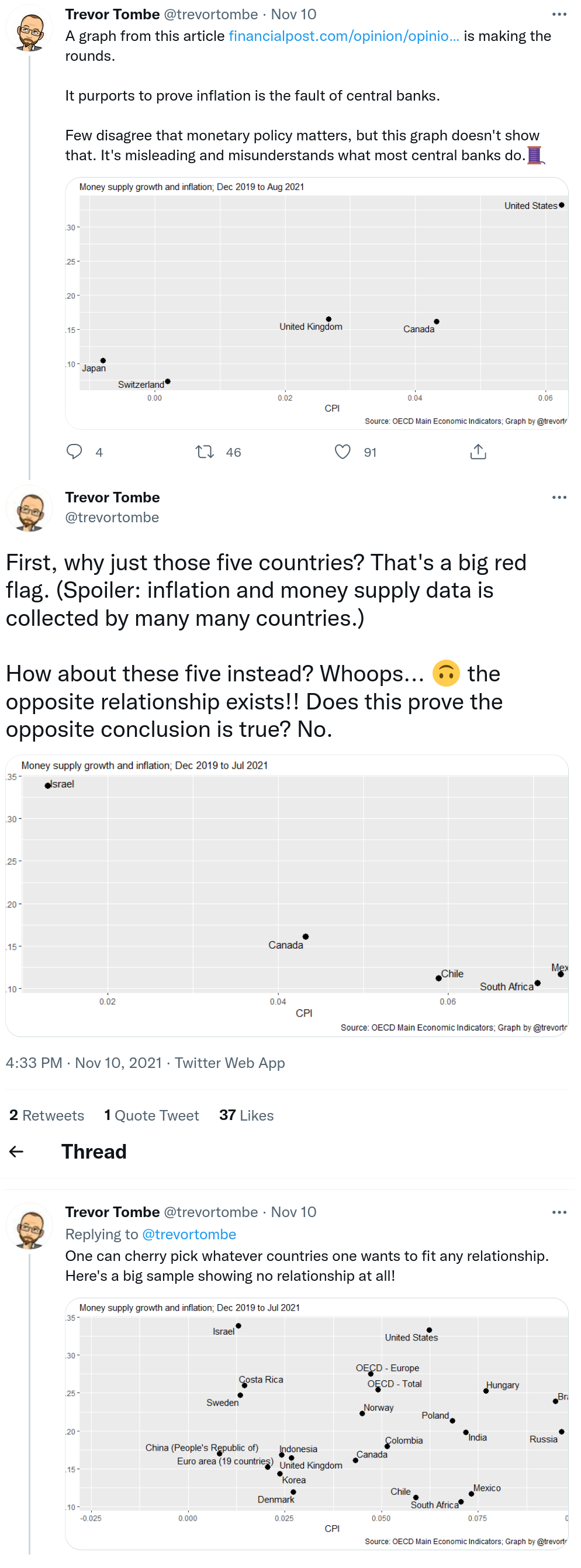

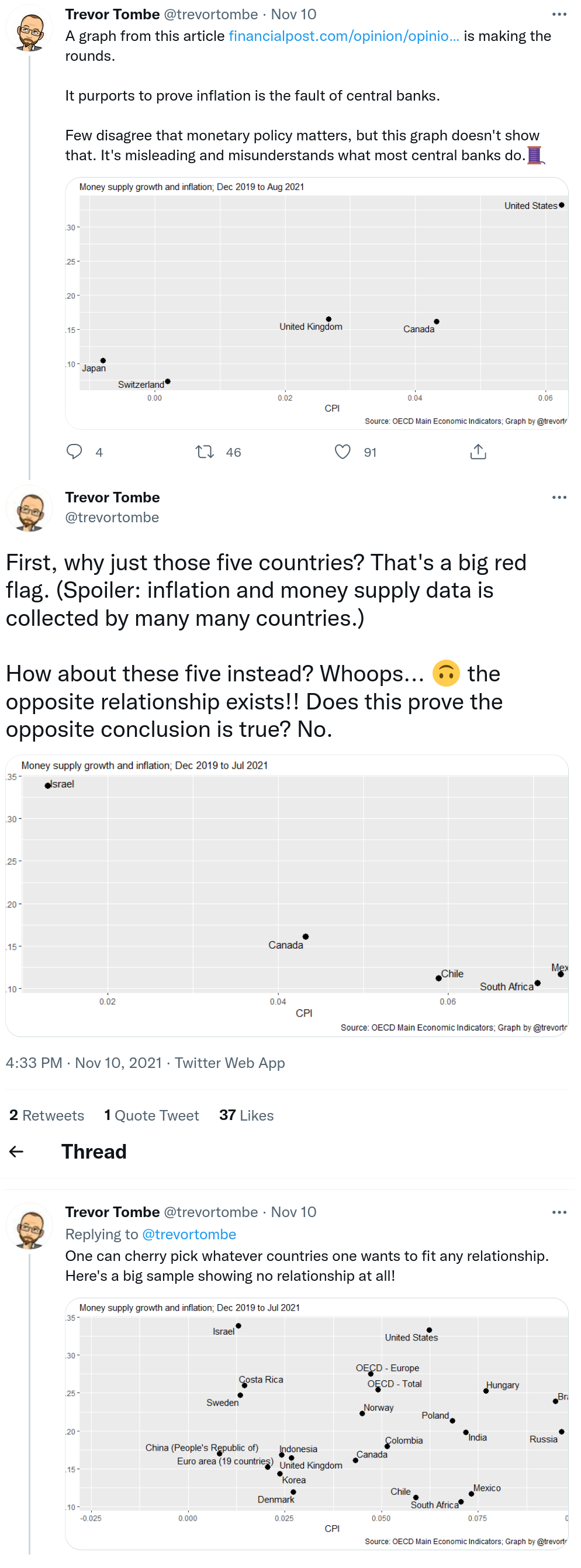

A simple graph demonstrating the relationship in a Financial Post commentary by Simon Fraser University economist Herbert Grubel [ Herbert Grubel is also a Senior Fellow at the neoliberal Fraser Institute; Grubel's article appears in The Financial Post, which is excluded as an information source on Persagen.com due to multiple issues (transphobia; association with American media; declining financials; Trumpism); ...].

The percentage increase in each country's consumer prices between December 2019 (before COVID-19) and August of 2021, paired with the percentage increase in its national M2 between December 2019 and July 2021. M2 is the most widely used indicator of the supply of money and a key determinant of national monetary conditions. The monetarist theory predicts that, all else equal, the greater the increase in the money supply, the greater future price increases will be.

The percentage increase in each country's consumer prices between December 2019 (before COVID-19) and August of 2021, paired with the percentage increase in its national M2 between December 2019 and July 2021. M2 is the most widely used indicator of the supply of money and a key determinant of national monetary conditions. The monetarist theory predicts that, all else equal, the greater the increase in the money supply, the greater future price increases will be.

[Source | local copy]

Herbert Grubel's post and graph (above) prompted the following response from the University of Calgary's Trevor Tombe, with a graph showing the exact opposite or no relationship at all.

A graph from this Financial Post article is making the rounds. It purports to prove inflation is the fault of central banks. Few disagree that monetary policy matters, but this graph doesn't show that. It's misleading and misunderstands what most central banks do.

A graph from this Financial Post article is making the rounds. It purports to prove inflation is the fault of central banks. Few disagree that monetary policy matters, but this graph doesn't show that. It's misleading and misunderstands what most central banks do.

[Source]

Complicating the picture in Canada are the billions of dollars being created out of thin air by the housing boom [Archive.today | local copy], as outlined in a short and sweet analysis by Canada's Library of Parliament.

"The majority of money in the economy is created by commercial banks when they extend new loans, such as mortgages," says the report, published in May 2021. As mortgage loans grow alongside soaring real estate values, the impact is much greater than central bank bond buying.

The idea that inflation is caused by a flood of money chasing a limited amount of goods, pushing up the price of those goods, has the virtue of feeling intuitively correct, but as our central bankers continually tell us, economies are not static. They say a little extra stimulus is still needed to use up spare capacity, making the economy stronger and more productive.

The trouble with trying to understand inflation - like trying to understand any complex system - is that human brains, not being omniscient, cannot comprehend all of the economy's working parts. And in such an interdependent system, it may be false to imagine there is a discrete cause or a simple solution.

At the beginning of last week, Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem was widely quoted as saying that Canadian inflation was "transitory but not short-lived."

By that measure, all inflation is transitory, because it comes for a while and then, months or years later, it disappears again.

But one thing many economists seem to agree upon is that in the short term, central bankers must begin to raise interest rates, probably sooner than they had planned only months ago.

As disruptive as they may be for those who believed the majority view just last year that inflation and rates would remain tame, rate hikes won't be an instant fix. Studies show their inflation-fighting power can take two years to come into full effect.

Politicization of Inflation

The issues discussed in the Inflation: Good or Bad? subsection (above) demonstrate the politicization of inflation. This is discussed in the following article.

[YesMagazine.org, 2021-11-22] Blowing Up a Few Myths About Inflation. | October's 6.2% inflation rate, while higher than it has been recently, doesn't measure up to our last inflationary crisis. | The response to inflation has become conflated with simplistic political positioning.

Inflation has been a bugaboo of right-wingers and even the political center since the 1970s. So it's not surprising that with consumer prices rising, the national discourse has suddenly shifted from yesterday's news to looming hyperinflation and fiscal ruin. But in order to understand what's really going on, you need to understand what inflation is, what it isn't, and where we actually are.

Starting in the 1980s, American politicians (from both parties, but driven by Reaganite Republicanism) have governed under the assumption that the peak annual inflation we had then was a product of too much government spending. Inflation peaked at about 14% annually in 1980, but the "great inflation" is often considered the period between 1965 and 1982, and it also includes such "externalities" as the Vietnam War, President Richard Nixon taking the U.S. off the gold standard, the political crisis surrounding Watergate scandal and Richars Nixon's resignation, and the massive oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 (both stemming primarily from instability in the Middle East).

Despite all those complicating factors, the conventional wisdom blamed President Jimmy Carter for failing to stem rising prices, especially of gasoline, ushering the era of inflation-phobia.

So are we currently on the cusp of runaway inflation or not?

October 2021's 6.2% inflation rate, while higher than it has been recently, doesn't measure up to our last inflationary crisis - at least not yet. While some pundits are wringing their hands about looming hyperinflation, their concerns are, shall we say, full of hot air. Hyperinflation is defined as inflation of at least 50% per month - the kind of crises afflicting 1920's Germany, 1940's Hungary, and 2000's Zimbabwe that coincide with a broader economic collapse. Those governments printed money to keep up with expenses, but with those nations' domestic economies in ruins, the money had nothing to buy, causing prices to skyrocket in a vicious cycle driven by too much demand for too little supply.

The U.S. is experiencing none of those conditions, and, indeed, the economy has been buoyed in the 21st century by emerging as the world's largest oil producer and as a net exporter of petroleum. The gross domestic product, as imperfect a measure of the whole economy as it is, has been growing since mid-2020, and the Federal Reserve has not taken any action in 2021 so far that demonstrates concern over inflation.

Even as oil production becomes increasingly unsustainable in the face of accelerating climate change and the rising costs of extraction, the U.S. dollar is still the top reserve currency in the world, unlikely to be supplanted by the euro, yuan, or Bitcoin. Even Donald Trump's reign of chaos couldn't dislodge the dollar from its perch atop the global financial system, or sidetrack the U.S. stock market. Job growth in 2021 has been generally good (revised statistics keep pushing the job numbers higher), and Goldman Sachs is now predicting that recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a 50-year-low unemployment rate - 3.5% - by the end of 2022.

In other words, we're seeing some consumer price inflation, but the economic fundamentals appear to be sound. So what's really going on?

In short, misdirection. today's Republican Party has become a party of opposition to anything that could be considered a Democratic "win." Look no further than the intra-GOP strife over the votes for President Joe Biden's bipartisan infrastructure bill [Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act]. When congressional Republicans are receiving death threats from constituents for supporting a bill their own party had a hand in crafting, it's yet one more sign of a party that has gone off the deep end. (There's a similar dynamic playing out with Republicans holding the economy hostage over the debt ceiling. We can expect more fireworks on that in December 2021.)

But infrastructure plan notwithstanding, Joe Biden's got a few more agenda items, notably his Build Back Better Plan, a much-overdue investment in the social safety net that includes such necessary programs as paid family leave, universal preschool, extension of the child tax credit that has kept families afloat during the COVID-19 pandemic, investments in clean energy and climate programs, and more.

The Republicans are universally opposed to all of those programs, so the Democrats bundled them into a budget reconciliation package that could pass the United States Senate by a simple majority. That entails having the entire caucus unified, however, which hasn't happened yet, and time is running out to act this year [2021].

The sticking point in the plan, some conservative Democrats say, is the cost - and now, inflationary fears. In fact, a lot of the media coverage of the plan focuses on the total price tag, some $1.75 trillion, which is indeed a huge amount, even if it's half the size of Biden's initial $3.5 trillion proposal. The message is still the same 40-year-old line that more government spending equals more inflation.

But that's an overly simplistic argument to make. Setting aside the political machinations behind this argument, it fails to take into account that Biden's plan, as originally proposed, would have been paid for with tax increases and therefore would not have led to any net spending increase. Most of those tax increases were on the very wealthy, however, which naturally made the entire Republican Party line up against it and exposed a few Democrats' primary allegiances to big business [e.g.: Joe Manchin].

This argument also overlooks the fact that the spending for the reconciliation bill would be spread out over 10 years, amounting to $175 billion per year. Considering that the U.S. government budget for 2020 contained $6.6 trillion in spending, saying that increasing that spending by about 2.7% will lead to economic catastrophe is a touch hyperbolic, if not divorced from past experience (Trump's 2020 budget spending plan was a 33.3% increase over his $4.4 trillion 2019 budget, while revenues dropped to $3.4 trillion from $3.5 trillion). In addition, the U.S. GDP in the third quarter of 2020 stood at more than $23 trillion, meaning that new proposed spending would barely make a dent in the overall economy.

But the plan's effects would definitely be felt by those who need it most: the poor, the working class, parents of young children, the elderly - exactly the sort of people whom Democrats hope to win or maintain as voters in their coalition. The Democratic Party is legendarily bad at messaging, however, and it's done a poor job of selling exactly what's in the Build Back Better Plan. That's allowed Republicans to frame the entire debate as one over trillions in government spending, which in their narrative is entirely wasteful.

Inflation has become the latest excuse trotted out to try and sideline this agenda. Even a couple of conservative Democrats are using inflation as an excuse to try to kill, delay, or water down the bill even more than they have already, probably fearing that Republicans will use their vote for more spending as fodder for campaign ads. (Spoiler alert: They'll do that no matter how the Democrats vote. Truth isn't a factor in GOP messaging.)

None of this is to say that inflation can't or won't be a concern. When prices go up, consumers feel the pinch. But the response to inflation has become conflated with simplistic political positioning, instead of being approached as a complex economic problem to solve.

Consider gasoline prices, which have seen some of the largest price increases lately. What you pay at the pump isn't set by the White House. Prices can vary greatly by region, and even within states. According to GasBuddy, which reports the cheapest gas available in any given market, the lowest price at the pump in Texas on 2021-11-16 was $2.29 per gallon in Baytown, near Houston, Texas. Prices were significantly higher ($2.76-$2.79) in the Austin area, higher still in Dallas (up to $2.83), and up to $3.05 in El Paso. In Illinois, the lowest price in the entire state starts at $3.12 per gallon, and Californians can expect to pay nearly $4 per gallon or more.

(Gasoline in the U.S. is also heavily subsidized, keeping our prices artificially low. High prices are a global issue, with Europeans frequently paying the equivalent of $4-$5 per gallon.)

Other consumer products, such as automobiles and food, have also been getting more expensive. Global supply chains are still being disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. But these - both the prices of imports and the effects of the virus on the shipping industry - are also largely outside the control of the government. Even if backlogged consumer products make it off jammed-up container ships into port, the U.S. is also experiencing a shortage in long-range truckers, preventing many products from getting to markets. New cars, another product with volatile prices, are dependent on semiconductor chips that have been in short supply - a factor of global trade, rising tensions between the U.S. and China, and a lengthy production cycle. And those semiconductor chips also power (and are slowing production and sales of) computers, phones, manufactured industrial materials, and appliances. Good luck getting a new PlayStation 5 in time for Christmas.

The two principal tools the U.S. government has for controlling inflation are the money supply and interest rates. With the former, there isn't a direct correlation - X dollars in the economy leads to Y% inflation. Inflation is instead a factor of how much money there is in circulation relative to the amount of products it can buy. A rise in prices caused by a continued shortage in consumer products, amplified by the ongoing disruptions to the global supply chain from the pandemic, can be intensified by a lot of new money flooding the economy. But even while some prices are going up, we're not dealing with critical shortages of basic needs (at least, none that are new; our housing market has been a mess for years).

But what is also true is that the investments in the social safety net would put money in the pockets of Americans, not big banks, and Americans, in turn, will use that money for food, bills, child care, or other needs. In other words, that money will circulate and boost the economy, allowing what inflation we have to be more easily absorbed. Leaving Americans destitute in the face of rising prices is both counterproductive and cruel.

And, in the grand scheme of things, we're not talking about that much money. A trillion dollars only sounds like a lot until you realize just how many more trillions are already out there. Biden's agenda is more about reallocating tax revenue and reprioritizing spending, rather than just letting the printing presses run wild.

Furthermore, interest rates have been at historic lows since the end of the Great Recession. Despite the warnings of inflation from many of the usual suspects, we haven't seen any of those omens of doom come true yet. If things start heating up too much, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors has a lot of room to maneuver to cool things down. It's keeping an eye on inflation, and so far, the Fed isn't too worried about it, so we shouldn't be either. What is worrisome is how much politics is intruding into this discussion. People who know better (and, let's face it, many who don't) are picking up on inflation as a problem that requires a political solution, a "solution" that will harm poor communities and marginalized communities more and allow the rich to keep their wealth safely out of public reach. We can't afford to get distracted in this debate.

Additional Reading

[CBC.ca, 2022-01-12] U.S. inflation rises to yet another 40-year high of 7%. Higher than previous month's high of 6.8% and in line with expectations.

[RobertReich.org, 2021-12-18] Psst: You want to know what’s really driving inflation? (Not what the Fed thinks it is.). | Reblogged: [CommonDreams.org, 2021-12-21] What's Driving Higher Prices? Unchecked Corporate Power. The real reason for inflation is clear: the increasing concentration of the American economy into the hands of a relative few corporate giants with the power to raise prices.

[theRealNews.com, 2021-12-09] "The elites need a new bogeyman," and that bogeyman is inflation. Just like past overblown fears about the US budget deficit, today's panic over inflation is being cynically used by political and corporate elites to stop the government from actually helping people.

"After years of hypocrisy and bungled forecasts of doom, the budget deficit [National debt of the United States, i.e, U.S. budget deficit)] no longer provokes panic," economist Max B. Sawicky [local copy] recently wrote in In These Times. "The elites need a new bogeyman, otherwise Congress [United States Congress] might actually spend us into happiness. Now, the new monster in the closet is inflation." With all eyes on President Joe Biden's Build Back Better Plan - which would entail massive and sorely needed social investments in education, healthcare, childcare, clean energy, and more - a familiar chorus of budgetary hand wringers has emerged to argue that such social spending is the cause of increased inflation. As Max Sawicky argues, that's nonsense.

In this segment of The Marc Steiner Show, now available in video form, Marc Steiner and Max Sawicky break down the current levels of inflation and discuss the political motivations behind the moral panic over inflation - which is essentially a new form of old-school deficit hawkery.

Max Sawicky is an economist, writer, and senior research fellow at the Center for Economic and Policy Research; Max Sawicky has worked at the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, the Economic Policy Institute, and the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

[North99.org, 2020-04-09] Fraser Institute Defends Price-Gouging Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. The Right-Wing Think Tank Argues That the Practice Is "Socially Beneficial."

Return to Persagen.com