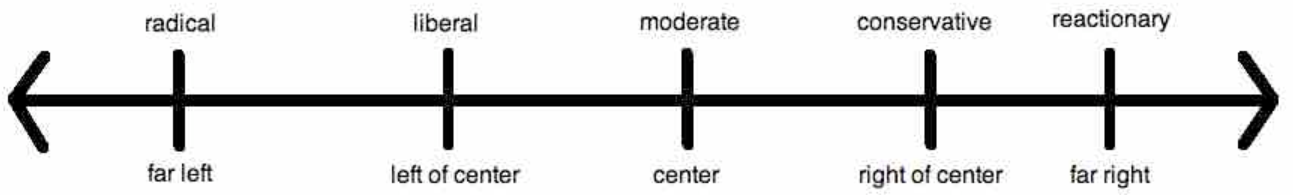

Traditional political spectrum

Source |

|

Political spectrum

Source |

| URL | https://Persagen.com/docs/political_ideologies-and-economic_systems.html |

| Sources | Persagen.com | Wikipedia | other sources (cited in situ) |

| Source URL | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_spectrum |

| Date published | 2021-09-24 |

| Curation date | 2021-09-24 |

| Curator | Dr. Victoria A. Stuart, Ph.D. |

| Modified | |

| Editorial practice | Refer here | Date format: yyyy-mm-dd |

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more geometric axes that represent independent political dimensions. The expressions political compass and political map are used to refer to the political spectrum as well, especially to popular two-dimensional models of it.

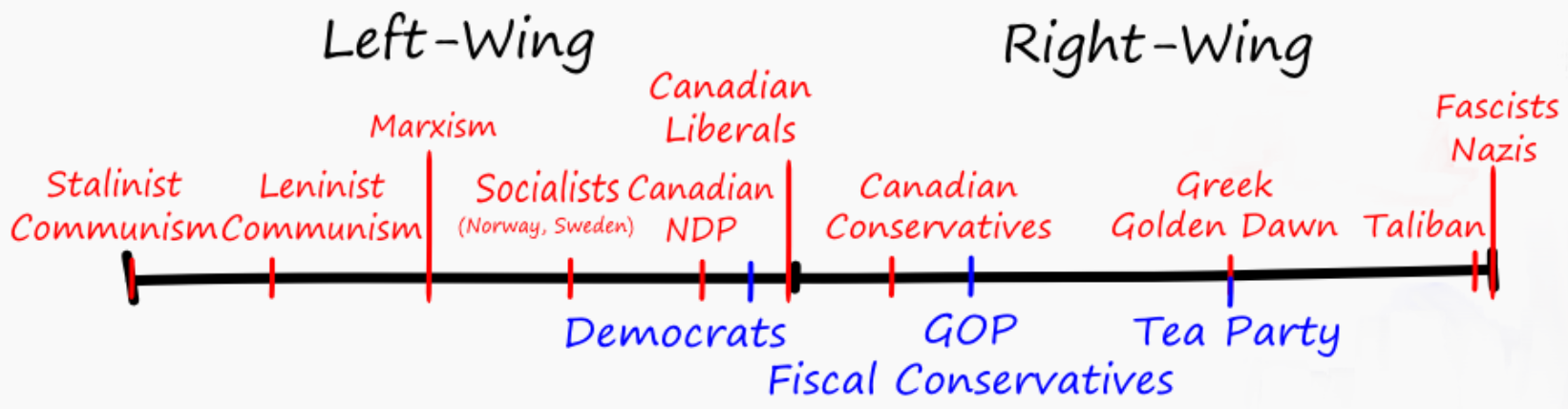

Most long-standing spectra include the left-right dimension which originally referred to seating arrangements in the French parliament after the French Revolution (1789-1799), with radicals on the left and aristocrats on the right. While communism and socialism are usually regarded internationally as being on the left, conservatism and reactionism are generally regarded as being on the right.

Liberalism can mean different things in different contexts, being sometimes on the left (social liberalism) and other times on the right (conservative liberalism or classical liberalism). Those with an intermediate outlook are sometimes classified as centrists. Politics that rejects the conventional left-right political spectrum is often known as syncretic politics, although the label tends to mischaracterize positions that have a logical location on a two-axis spectrum because they seem randomly brought together on a one-axis left-right spectrum.

Political scientists have frequently noted that a single left-right axis is too simplistic and insufficient for describing the existing variation in political beliefs and included other axes. Although the descriptive words at polar opposites may vary, the axes of popular biaxial spectra are usually split between economic issues (on a left-right dimension) and socio-cultural issues (on an authority-liberty dimension).

Far-left politics are politics further to the left of the left-right political spectrum than the standard political left.

There are different definitions of the far-left. Some scholars define it as representing the left of social democracy while others limit it to anarchism, socialism, and communism (or any derivative of Marxism-Leninism). In certain instances, especially in the news media, the term characterizes groups that advocate for revolutionary anti-capitalism and anti-colonialism.

Extremist far-left politics can involve violent acts such as terrorism and the formation of far-left militant organizations meant to abolish capitalist systems and the upper ruling class. Far-left terrorism consists of groups that attempt to realize their radical ideals and bring about change through violence rather than established political processes.

Notable left-wing movements:

Left-wing politics supports social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition of social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in society whom its adherents perceive as disadvantaged relative to others as well as a belief that there are unjustified inequalities that need to be reduced or abolished. According to emeritus professor of economics Barry Clark, left-wing supporters "claim that human development flourishes when individuals engage in cooperative, mutually respectful relations that can thrive only when excessive differences in status, power, and wealth are eliminated."

Within the left-right political spectrum, Left and Right were coined during the French Revolution (1789-1799), referring to the seating arrangement in the French Estates General. Those who sat on the left generally opposed the Ancien Régime and the Bourbon monarchy and supported the French Revolution, the creation of a democratic republic and the secularisation of society while those on the right were supportive of the traditional institutions of the Old Regime. Usage of the term Left became more prominent after the restoration of the French monarchy in 1815, when it was applied to the Independents. The word wing was first appended to Left and Right in the late 19th century, usually with disparaging intent, and left-wing was applied to those who were unorthodox in their religious or political views.

The term Left was later applied to a number of movements, especially republicanism in France during the 18th century, followed by socialism, including anarchism, communism, the labour movement, Marxism, social democracy, and syndicalism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Since then, the term left-wing has been applied to a broad range of movements, including the civil rights movement, feminist movement, LGBT rights movement, anti-war movement, and environmental movement - as well as a wide range of political parties.

"Left-wing politics in the United States"

Center-left politics (British English: centre-left politics) - also referred to as moderate-left politics - are political views that lean to the left-wing on the left-right political spectrum, but closer to the center than other left-wing politics. Those on the center-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The center-left promotes a degree of social equality that it believes is achievable through promoting equal opportunity. The center-left emphasizes that the achievement of equality requires personal responsibility in areas in control by the individual person through their abilities and talents as well as social responsibility in areas outside control by the person in their abilities or talents.

The center-left opposes a wide gap between the rich and the poor and supports moderate measures to reduce the economic gap, such as a progressive income tax, laws prohibiting child labour, minimum wage laws, laws regulating working conditions, limits on working hours and laws to ensure the workers' right to organize. The center-left typically claims that complete equality of outcome is not possible, but instead that equal opportunity improves a degree of equality of outcome in society.

In Europe, the center-left includes social democrats, progressives, and also some democratic socialists, greens, and the Christian left. Some variants of liberalism, especially social liberalism, are described as center-left, but many social liberals are in the center of the political spectrum as well.

Centrism is a political outlook or position that involves acceptance and/or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy, while opposing political changes which would result in a significant shift of society strongly to either the left or the right.

Both center-left politics and center-right politics involve a general association with Centrism that is combined with leaning somewhat to their respective sides of the left-right political spectrum. Various political ideologies, such as Christian democracy, and certain forms of social liberalism and classical liberalism, can be classified as centrist ones, as can the Third Way, a modern political movement that attempts to reconcile right-wing politics and left-wing politics by advocating for a synthesis of center-right economic platforms with some center-left social policies.

Center-right politics (British English: centre-right politics) - also referred to as moderate-right politics - lean to the right of the political spectrum, but are closer to the center than others. From the 1780s to the 1880s, there was a shift in the Western world of social class structure and the economy, moving away from the nobility and mercantilism, toward the upper class and capitalism. This general economic shift toward capitalism affected center-right movements, such as the Conservative Party of the United Kingdom, which responded by becoming supportive of capitalism.

The International Democrat Union is an alliance of center-right (as well as some further right-wing) political parties - including the UK Conservative Party, the Conservative Party of Canada, the Republican Party of the United States, the Liberal Party of Australia, the New Zealand National Party, and Christian democratic parties - which declares commitment to human rights as well as economic development.

Ideologies characterised as center-right include liberal conservatism and some variants of liberalism and Christian democracy, among others. The economic aspects of the modern center-right have been influenced by economic liberalism, generally supporting free markets, limited government spending, and other policies heavily associated with neoliberalism. The moderate right is neither universally socially conservative nor culturally liberal, and often combines both beliefs with support for civil liberties and elements of traditionalism.

Historical examples of center-right schools of thought include One Nation Conservatism in the United Kingdom, Red Tories in Canada, and Rockefeller Republicans in the United States. New Democrats also embraced several aspects of center-right policy, including balanced budgets, free trade, and welfare reform. These ideological factions contrast with far right policies and right-wing populism. They also tend to be more supportive of cultural liberalism and green conservatism than right-wing variants.

According to a 2019 study, center-right parties had approximately 27% of the vote share in 21 Western democracies in 2018. This was a decline from 37% in 1960.

Source: Wikipedia, 2021-09-26

Right-wing politics supports the view that certain social orders and hierarchies are inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, or tradition. Hierarchy and inequality may be seen as natural results of traditional social differences or competition in market economies.

The term right-wing can generally refer to the section of a political party or system that advocates free enterprise and private ownership, and typically favours socially traditional ideas.

In Europe, economic conservatives are usually considered liberal, and the Right includes nationalists, idealists,

Notable attributes:

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are politics further on the right of the left-right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being anti-communist, authoritarian, ultranationalist, and having

Historically used to describe the experiences of fascism and Nazism, today far-right politics include neo-fascism, Neo-Nazism, the Third Position, the alt-right, racial supremacism, and other ideologies or organizations that feature aspects of ultranationalist, chauvinist, xenophobic, theocratic, racist, homophobic, transphobic, or reactionary views.

Far-right politics has led to oppression, political violence, forced assimilation, ethnic cleansing, or genocide against groups of people based on their supposed inferiority, or their perceived threat to the native ethnic group, nation, state, national religion, dominant culture, or conservative social institutions.

Anarchism is a political philosophy and political movement that is sceptical of authority and rejects all involuntary, coercive forms of hierarchy. Anarchism calls for the abolition of the state - which it holds to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful. As a historically left-wing movement, placed on the farthest left of the political spectrum, anarchism is usually described alongside libertarian Marxism as the libertarian wing (libertarian socialism) of the socialist movement, and has a strong historical association with anti-capitalism and socialism.

The history of anarchism goes back to

Anarchism employs a diversity of tactics in order to meet its ideal ends which can be broadly separated into revolutionary and evolutionary tactics; there is significant overlap between the two, which are merely descriptive. Revolutionary tactics aim to bring down authority and state, having taken a violent turn in the past, while evolutionary tactics aim to prefigure what an anarchist society would be like. Anarchist thought, criticism, and praxis have played a part in diverse areas of human society. Anarchism has been both defended and criticised; criticism of anarchism include claims that it is internally inconsistent, violent, or utopian.

Authoritarianism is a form of government characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of a strong central power to preserve the political status quo, and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voting. Political scientists have created many typologies describing variations of authoritarian forms of government. Authoritarian regimes may be either autocratic or oligarchic in nature and may be based upon the rule of a party or the military.

In an influential 1964 work, the political scientist Juan Linz defined authoritarianism as possessing four qualities:

Limited political pluralism, realized with constraints on the legislature, political parties, and interest groups.

Political legitimacy based upon appeals to emotion and identification of the regime as a necessary evil to combat "easily recognizable societal problems, such as underdevelopment or insurgency."

Minimal political mobilization, and suppression of anti-regime activities.

Ill-defined executive powers, often vague and shifting, which extends the power of the executive.

Minimally defined, an authoritarian government lacks (a) free and competitive direct elections to legislatures, (b) free and competitive direct or indirect elections for executives, or both. Broadly defined, authoritarian states include countries that lack civil liberties such as freedom of religion, or countries in which the government and the political opposition do not alternate in power at least once following free elections. Authoritarian states might contain nominally democratic institutions such as political parties, legislatures and elections which are managed to entrench authoritarian rule and can feature fraudulent, non-competitive elections. Since 1946, the share of authoritarian states in the international political system increased until the mid-1970s, but declined from then until the year 2000.

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject to neither external legal restraints nor regularized mechanisms of popular control (except perhaps for the implicit threat of coup d'état or other forms of rebellion).

In earlier times, the term autocrat was coined as a favorable description of a ruler, having some connection to the concept of "lack of conflicts of interests" as well as an indication of grandeur and power. This use of the term continued into modern times, as the Russian Emperor was styled "Autocrat of all the Russias" as late as the early 20th century. In the 19th century, Eastern and Central Europe were under autocratic monarchies within the territories of which lived diverse peoples.

Communism (from Latin communis: "common, universal") is a philosophical, social, political, and economic ideology and movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, namely a socioeconomic order structured upon the ideas of common ownership of the means of production and the absence of social classes, money, and the state. Communism is a specific, yet distinct, form of socialism. Communists agree on the withering away of the state but disagree on the means to this end, reflecting a distinction between a more libertarian approach of communization, revolutionary spontaneity, and workers' self-management, and a more vanguardist or Communist party-driven approach through the development of a constitutional socialist state.

Variants of communism have been developed throughout history, including anarcho-communism, Leninism, Stalinism, and Maoism. Communism includes a variety of schools of thought which broadly include Marxism and libertarian communism, as well as the political ideologies grouped around both, all of which share the analysis that the current order of society stems from capitalism, its economic system and mode of production, namely that in this system there are two major social classes, the relationship between these two classes is exploitative, and that this situation can only ultimately be resolved through a social revolution. The two classes are the proletariat (the working class), who make up the majority of the population within society and must work to survive, and the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class), a small minority who derives profit from employing the working class through private ownership of the means of production. According to this analysis, revolution would put the working class in power and in turn establish social ownership of the means of production which is the primary element in the transformation of society towards a communist mode of production.

In the 20th century, Communist governments espousing Marxism-Leninism and its variants came into power in parts of the world, first in the Soviet Union with the Russian Revolution of 1917, and then in portions of Eastern Europe, Asia, and a few other regions after World War II. Along with social democracy, communism became the dominant political tendency within the international socialist movement by the 1920s. Criticism of communism can be divided into two broad categories, namely that which concerns itself with the practical aspects of 20th century Communist states and that which concerns itself with communist principles and theory. Several academics and economists, among other scholars, posit that the Soviet model under which these nominally Communist states in practice operated was not an actual communist economic model in accordance with most accepted definitions of communism as an economic theory but in fact a form of state capitalism, or non-planned administrative-command system.

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development - better known as historical materialism - to understand class relations and social conflict, as well as a dialectical perspective to view social transformation. Marxism originates from the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. As Marxism has developed over time into various branches and schools of thought, there is currently no single definitive Marxist theory.

Some Marxist schools of thought place greater emphasis on certain aspects of classical Marxism, while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Some schools have sought to combine Marxian concepts and non-Marxian concepts which has then led to contradictory conclusions. It has been argued that there is a movement toward the recognition of historical materialism and dialectical materialism as the fundamental conceptions of all Marxist schools of thought. This view is rejected by some post-Marxists such as Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, who claim that history is not only determined by the mode of production, but also by consciousness and will.

Marxism has had a profound impact on global academia, having influenced many fields, including anthropology, archaeology, art theory, criminology, cultural studies, economics, education, ethics, film theory, geography, historiography, literary criticism, media studies, philosophy, political science, psychology, science studies, sociology, urban planning, and theater.

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a

In

Marxism-Leninism is a communist ideology and was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. It was the formal name of the official state ideology adopted by the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various self-declared scientific socialist regimes in the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World during the Cold War, as well as the Communist International after Bolshevisation. Today, Marxism-Leninism is the ideology of several communist parties and remains the official ideology of the ruling parties of China, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam as unitary one-party socialist republics, and of Nepal in a multiparty democracy. Generally, Marxist-Leninists support proletarian internationalism and socialist democracy - and oppose anarchism, fascism, imperialism, and liberal democracy.

Marxism-Leninism holds that a two-stage communist revolution is needed to replace capitalism. A vanguard party, organised hierarchically through democratic centralism, would seize power "on behalf of the proletariat", and establish a communist party-led socialist state, which it claims to represent the dictatorship of the proletariat. The state controls the economy and means of production, suppresses the bourgeoisie, counter-revolution, and opposition, promotes collectivism in society, and paves the way for an eventual communist society, which would be both classless and stateless. Due to its state-oriented approach, Marxist-Leninist states have been commonly referred to by Western academics as Communist states.

As an ideology and practice, it was developed by Joseph Stalin in the 1920s based on his understanding and synthesis of orthodox Marxism and Leninism. After the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, Marxism-Leninism became a distinct movement in the Soviet Union when Stalin and his supporters gained control of the party. It rejected the common notions among Western Marxists of world revolution, as a prerequisite for building socialism, in favour of the concept of socialism in one country. According to its supporters, the gradual transition from capitalism to socialism was signified by the introduction of the first five-year plan and the 1936 Soviet Constitution. By the late 1920s, Stalin established ideological orthodoxy among the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), the Soviet Union, and the Communist International to establish universal Marxist-Leninist praxis. The formulation of the Soviet version of dialectical and historical materialism in the 1930s by Stalin and his associates, such as in Stalin's book Dialectical and Historical Materialism, became the official Soviet interpretation of Marxism, and was taken as example by Marxist-Leninists in other countries. In the late 1930s, Stalin's official textbook History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) (1938) popularised Marxism-Leninism as a term.

The internationalism of Marxist-Leninist socialism in one country was expressed in supporting revolutions in other countries, initially through the Communist International and then through the concept of socialist-leaning countries after de-Stalinisation. The establishment of other Communist states after World War II resulted in Sovietisation, and these Communist-led states tended to follow the Soviet Marxist-Leninist model of five-year plans and rapid industrialisation, political centralisation, and repression. During the Cold War, Marxism-Leninism was a driving force in international relations for most of the 20th century. With the death of Stalin and de-Stalinisation, Marxism-Leninism underwent several revisions and adaptations such as Guevarism, Ho Chi Minh Thought, Hoxhaism, Maoism, socialism with Chinese characteristics, and Titoism. This also caused several splits between Marxist-Leninist states, resulting in the Tito-Stalin split, the Sino-Soviet split, and the Sino-Albanian split. The socio-economic nature of Marxist-Leninist states, especially that of the Soviet Union during the Stalin era, has been much debated, varyingly being labelled a form of bureaucratic collectivism, state capitalism, state socialism, or a totally unique mode of production. The Eastern Bloc, including Marxist-Leninist states in Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Third World socialist regimes, have been variously described as "bureaucratic-authoritarian systems", and China's socio-economic structure has been referred to as "nationalistic state capitalism."

Criticism of Marxism-Leninism largely overlaps with criticism of communist party rule and mainly focuses on the actions and policies implemented by Marxist-Leninist leaders, most notably Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Pol Pot. In practice, Marxist-Leninist states have been marked by a high degree of centralised control by the state and communist party, political repression, state atheism, collectivisation, and use of forced labour and labour camps - as well as free universal education and healthcare, low unemployment and lower prices for certain goods. Historians such as Silvio Pons and Robert Service stated that repression and totalitarianism came from Marxist-Leninist ideology. Historians such as Michael Geyer and Sheila Fitzpatrick have put forward other explanations and criticise the focus on the upper levels of society and use of Cold War concepts such as totalitarianism which have obscured the reality of the system. While the emergence of the Soviet Union as the world's first nominally Communist state led to communism's widespread association with Marxism-Leninism and the Soviet model, several academics and economists, among other scholars, have stated that the Marxist-Leninist model was in practice a form of state capitalism, or a non-planned administrative-command system or command economy.

Adolf Hitler's policies and orders both directly and indirectly resulted in the deaths of about 50 million people in Europe. Benito Mussolini was a dictator who marked the beginning of "Fascism" in Europe.

A dictatorship is a form of government characterized by a single leader (dictator) or group of leaders that hold government power promised to the people and little or no toleration for political pluralism or independent media. In most dictatorships, the country's constitution promise citizens rights and the freedom to free and democratic elections; sometimes, it also mentions that all these aforementioned rights will be granted to the people, but this is not always the case. As democracy is a form of government in which "those who govern are selected through periodically contested elections (in years)", dictatorships are not democracies.

With the advent of the 19th and 20th centuries, dictatorships and constitutional democracies emerged as the world's two major forms of government, gradually eliminating monarchies with significant political power, the most widespread form of government in the pre-industrial era. Typically, in a dictatorial regime, the leader of the country is identified with the title of dictator; although, their formal title may more closely resemble something similar to leader. A common aspect that characterized dictatorship is taking advantage of their strong personality, usually by suppressing freedom of thought and speech of the masses, in order to maintain complete political and social supremacy and stability. Dictatorships and totalitarian societies generally employ political

Fascism is a form of far-right, authoritarian ultranationalism characterized by dictatorial power, forcible suppression of opposition, and strong regimentation of society and of the economy, which came to prominence in early 20th-century Europe. The first fascist movements emerged in Italy during World War I, before spreading to other European countries. Opposed to anarchism, democracy , liberalism, and Marxism, fascism is placed on the far right-wing within the traditional left-right spectrum.

Fascists saw World War I as a revolution that brought massive changes to the nature of war, society, the state, and technology. The advent of total war and the total mass mobilization of society had broken down the distinction between civilians and combatants. A military citizenship arose in which all citizens were involved with the military in some manner during the war. The war had resulted in the rise of a powerful state capable of mobilizing millions of people to serve on the front lines and providing economic production and logistics to support them, as well as having unprecedented authority to intervene in the lives of citizens.

Fascists believe that liberal democracy is obsolete and regard the complete mobilization of society under a totalitarian one-party state as necessary to prepare a nation for armed conflict and to respond effectively to economic difficulties. A fascist state is led by a strong leader (such as a dictator) and a martial law government composed of the members of the governing fascist party to forge national unity and maintain a stable and orderly society. Fascism rejects assertions that violence is automatically negative in nature and views imperialism, political violence and war as means that can achieve national rejuvenation. Fascists advocate a mixed economy, with the principal goal of achieving autarky (national economic self-sufficiency) through protectionist and economic interventionist policies. The extreme authoritarianism and nationalism of fascism often manifests a belief in racial purity or a master race, usually synthesized with some variant of racism or bigotry of a demonized "Other"; the idea of racial purity has motivated fascist regimes to commit massacres, forced sterilizations, genocides, mass killings, or forced deportations against a perceived "Other".

Since the end of World War II in 1945, few parties have openly described themselves as fascist, and the term is instead now usually used pejoratively by political opponents. The descriptions of neo-fascist or post-fascist are sometimes applied more formally to describe contemporary parties of the far-right with ideologies similar to, or rooted in, 20th-century fascist movements.

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sentiment as well as opposition to liberal democracy, parliamentarianism, liberalism, Marxism, communism, and socialism.

Allegations that a group is neo-fascist may be hotly contested, especially when the term is used as a political epithet. Some post-World War II regimes have been described as neo-fascist due to their authoritarian nature, and sometimes due to their fascination with and sympathy towards fascist ideology and rituals. Post-fascism is a label that has been applied to several European political parties which espouse a modified form of fascism and participate in constitutional politics.

Imperialism is a policy or ideology of extending the rule over peoples and other countries, for extending political and economic access, power and control, often through employing hard power, especially military force, but also soft power. While related to the concepts of colonialism and empire, imperialism is a distinct concept that can apply to other forms of expansion and many forms of government.

Oligarchy (from Greek "ὀλιγαρχία" ("oligarkhía"); from "ὀλίγος" ("olígos") "few", and "ἄρχω" ("arkho") "to rule or to command") is a form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, religious, political, or military control.

Throughout history, oligarchies have often been tyrannical, relying on public obedience or oppression to exist. Aristotle pioneered the use of the term as meaning rule by the rich, for which another term commonly used today is plutocracy. In the early 20th century Robert Michels developed the theory that democracies, like all large organizations, have a tendency to turn into oligarchies. In his "Iron law of oligarchy", Robert Michels suggests that the necessary division of labor in large organizations leads to the establishment of a ruling class mostly concerned with protecting their own power.

See also:

A plutocracy (Greek: "πλοῦτος", "ploutos", "wealth" and "κράτος", "kratos", "power") or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike systems such as democracy, liberalism, socialism, communism, or anarchism, plutocracy is not rooted in an established political philosophy.

Theocracy is a form of government in which a deity of some type is recognized as the supreme ruling authority, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries that manage the day-to-day affairs of the government.

Leaders who have been described as totalitarian rulers include Joseph Stalin (former General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union); Adolf Hitler (former Führer of Nazi Germany); Mao Zedong (former Chairman of the Communist Party of China); Benito Mussolini (former Prime Minister of Fascist Italy); and Kim Il-sung (the Eternal President of the Republic of North Korea).

Totalitarianism is a concept which is used in academia and politics to describe a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high degree of control over public and private life. It is regarded as the most extreme and complete form of authoritarianism. In totalitarian states, political power is often held by autocrats, such as dictators and absolute monarchs, who employ all-encompassing campaigns in which

As a political ideology, totalitarianism is a distinctly modernist phenomenon, and it has complex historical roots. Philosopher Karl Popper traced its roots to Plato, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's conception of the state, and the political philosophy of Karl Marx - although his conception of totalitarianism has been criticized in academia, and remains highly controversial. Other philosophers and historians such as Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer trace the origin of totalitarian doctrines to the Age of Enlightenment, especially to the anthropocentrist idea that "Man has become the master of the world, a master unbound by any links to nature, society, and history." In the 20th century, the idea of absolute state power was first developed by Italian Fascists, and concurrently in Germany by a jurist and Nazi academic named Carl Schmitt during the Weimar Republic in the 1920s. The founder of Italian Fascism, Benito Mussolini, defined fascism as such: "Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state." Schmitt used the term Totalstaat (literally "Total state") in his influential 1927 work titled The Concept of the Political, which described the legal basis of an all-powerful state.

Totalitarian regimes are different from other authoritarian regimes, as the latter denotes a state in which the single power holder, usually an individual dictator, a committee, a military junta, or an otherwise small group of political elites, monopolizes political power. A totalitarian regime may attempt to control virtually all aspects of social life, including the economy, the education system, arts, science, and the private lives and morals of citizens through the use of an elaborate ideology. It can also mobilize the whole population in pursuit of its goals.

A tyrant (from Ancient Greek "τύραννος", "tyrannos"), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to repressive means. The original Greek term meant an absolute sovereign who came to power without constitutional right, yet the word had a neutral connotation during the Archaic and early Classical periods. However, Greek philosopher Plato saw tyrannos as a negative word, and on account of the decisive influence of philosophy on politics, its negative connotations only increased, continuing into the Hellenistic period.

The philosophers Plato and Aristotle defined a tyrant as a person who rules without law, using extreme and cruel methods against both his own people and others. The Encyclopédie defined the term as a usurper of sovereign power who makes "his subjects the victims of his passions and unjust desires, which he substitutes for laws". In the late fifth and fourth centuries BC, a new kind of tyrant, one who had the support of the military, arose - specifically in Sicily.

One can apply accusations of tyranny to a variety of types of government:

to government by one individual (in an autocracy)

to government by a minority (in an oligarchy, tyranny of the minority)

to government by a majority (in a democracy, tyranny of the majority)

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production, and their operation for economic profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, a price system, private property - and the recognition of property rights, voluntary exchange, and wage labor. In a capitalist market economy, decision-making and investments are determined by owners of wealth, property, or production ability in capital and financial markets - whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.

Economists, historians, political economists and sociologists have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include Laissez-faire or free-market capitalism, state capitalism, and welfare capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership, obstacles to free competition, and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets and the role of intervention and regulation, as well as the scope of state ownership, vary across different models of capitalism. The extent to which different markets are free and the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most of the existing capitalist economies are mixed economies that combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.

Market economies have existed under many forms of government and in many different times, places and cultures. Modern capitalist societies developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the Industrial Revolution. Capitalist systems with varying degrees of direct government intervention have since become dominant in the Western world, and continue to spread. Economic growth is a characteristic tendency of capitalist economies.

Critics of capitalism argue that it concentrates power in the hands of a minority capitalist class that exists through the exploitation of the majority working class and their labor; prioritizes profit over social good, natural resources and the environment; is an engine of inequality, corruption and economic instabilities; is anti-democratic; and that many are not able to access its purported benefits and freedoms, such as freely investing. Supporters argue that it provides better products and innovation through competition, promotes pluralism and decentralization of power, disperses wealth to people who are able to invest in useful enterprises based on market demands, allows for a flexible incentive system where efficiency and sustainability are priorities to protect capital, creates strong economic growth, and yields productivity and prosperity that greatly benefit society.

The Christian left is a range of center-left and left-wing left-wing Christian political and Christian social movements that largely embrace social justice viewpoints and uphold a social doctrine or social gospel.

Given the inherent diversity in international political thought, the term Christian left can have different meanings and applications in different countries. While there is much overlap, the Christian left is distinct from liberal Christianity, meaning not all Christian leftists are liberal Christians and vice versa. Christian anarchism, Christian communism, and Christian socialism are subsects of the socialist Christian left, although it also includes more moderate Christian left-liberal and social-democratic viewpoints.

The Christian right (the religious right) are Christian political factions that are characterized by their strong support of socially conservative policies. Christian conservatives seek to influence politics and public policy with their interpretation of the teachings of Christianity.

In the United States, the Christian right is an informal coalition formed around a core of conservative evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics. The Christian right draws additional support from politically conservative mainline Protestants and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. The movement has its roots in American politics going back as far as the 1940s and has been especially influential since the 1970s. Its influence draws from grassroots activism as well as from focus on social issues and the ability to motivate the electorate around those issues.

The Christian right is notable for advancing socially conservative positions on issues including school prayer, intelligent design, embryonic stem cell research, homosexuality, euthanasia, contraception, sex education, abortion, and pornography. Although the term Christian right is most commonly associated with politics in the United States, similar Christian conservative groups can be found in the political cultures of other Christian-majority nations.

Cultural conservatism is described as the protection of the cultural heritage of a nation state, or of a culture not defined by state boundaries. Cultural conservatism is sometimes concerned with the preservation of a language, such as French in Quebec (Canada), and other times with the preservation of an ethnic group's culture such as Native Americans [indigenous peoples].

In the United States, the term cultural conservative may imply a conservative position in the culture wars. Because cultural conservative (according to the compass theory) expresses the social dimension of

Fiscal conservatism is a political philosophy and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility advocating low taxes, reduced government spending, and minimal government debt. Deregulation, free trade, privatization, and tax cuts are the defining qualities of fiscal conservatism. Fiscal conservatism follows the same philosophical outlook of classical liberalism.

The term fiscal conservatism has its origins in the era of the American New Deal during the 1930s as a result of the policies initiated by modern liberals [social liberals], when many classical liberalism started calling themselves

Fiscal conservatives form one of the three legs of the traditional American

Because of its close proximity to the United States, the term fiscal conservative has entered the lexicon in Canada. In many other countries, economic liberalism - or simply liberalism - is used to describe what Americans call fiscal conservatism.

Movement conservatism is an inside term describing

R. Emmett Tyrrell, a prominent right-wing writer, says, "the conservatism that, when it made its appearance in the early 1950s, was called the New Conservatism and for the past fifty or sixty years has been known as 'movement conservatism' by those of us who have espoused it." Political scientists Doss and Roberts say that "The term movement conservatives refers to those people who argue that big government constitutes the most serious problem.... Movement conservatives blame the growth of the administrative state for destroying individual initiative." Historian Allan J. Lichtman traces the term to a memorandum written in February 1961 by William A. Rusher, the publisher of National Review, to William F. Buckley Jr., envisioning National Review as not just "the intellectual leader of the American Right," but more grandly of "the Western Right." Rusher envisioned philosopher kings would function as "movement conservatives".

Recent examples of writers using the term "movement conservatism" include Sam Tanenhaus, Paul Gottfried, and Jonathan Riehl. The New York Times columnist Paul Krugman devoted a chapter of his book The Conscience of a Liberal (2007) to the movement, writing that movement conservatives gained control of the Republican Party starting in the 1970s and that Ronald Reagan was the first movement conservatism elected president.

[theConversation, 2022-02-13] Canada should be preparing for the end of American democracy.

[Straight.com, 2022-02-07] Right-wing backlash on display in both the federal Conservative and B.C. Liberal parties.

[theNation.com, 2021-11-26] Who Is the University of Austin For? The project's uphill battle points to a deeper contradiction within what might be called neo-neoconservatism.

[theAtlantic.com, 2021-11-18] The Terrifying Future of the American Right. What I saw at the National Conservatism Conference.

[MotherJones.com, 2021-11-26] How Dangerous Is Peter Thiel? In a recent speech, the tech billionaire gave us a frightening look at his worldview.

[19thNews.org, 2021-11-16] Librarians are resisting censorship of children's books by LGBTQ+ and Black authors. Attempts to keep books out of school libraries aren't new, but there has been a recent increase in political challenges to literature.

[NPR.org, 2021-11-13] More Republican leaders try to ban books on race, LGBTQ issues.

Traditionalist conservatism, also referred to as classical conservatism, traditional conservatism or traditionalism, is a political philosophy and moral philosophy emphasizing the need for the principles of a transcendent moral order, manifested through certain natural laws to which society ought to conform in a prudent manner. Traditionalist conservatism is based on the political philosophies of Aristotle and Edmund Burke. Traditionalists emphasize the bonds of social order and the defense of ancestral institutions over what it considers excessive individualism.

Traditionalist conservatism places a strong emphasis on the notions of custom, convention, and tradition. Theoretical reason is derided, and is considered against practical reason. The state is also seen as a communal enterprise with spiritual and organic qualities. Traditionalists believe that any change is not the result of intentional reasoned thought but flows naturally out of the traditions of the community. Leadership, authority and hierarchy are seen as natural products. Traditionalism developed throughout 18th-century Europe, particularly as a response to the disorder of the English Civil War, and the radicalism of the French Revolution. In the middle of the 20th century, traditionalist conservatism started to organize itself in earnest as an intellectual and political force.

Democracy (Greek: "δημοκρατία", "dēmokratiā", from "dēmos" "people" and "kratos" "rule") is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choose governing officials to do so ("representative democracy"). In each case the process is free (as in people can make the choice freely, they or the candidate can advocate for their position(s) through speech and assembly and people can form organizations to advocate for their positon(s)). Who is considered part of "the people" and how authority is shared among or delegated by the people has changed over time and at different rates in different countries, but over time more and more of a democratic country's inhabitants have generally been included. Cornerstones of democracy include freedom of assembly, freedom of association and freedom of speech, inclusiveness and equality, membership, consent, voting, right to life, and minority rights

The notion of democracy has evolved over time considerably. The original form of democracy was a direct democracy. The most common form of democracy today is a representative democracy, where the people elect government officials to govern on their behalf such as in a parliamentary democracy or presidential democracy.

Prevalent day-to-day decision making of democracies is the majority rule, though other decision making approaches like supermajority and consensus have also been integral to democracies. They serve the crucial purpose of inclusiveness and broader legitimacy on sensitive issues - counterbalancing majoritarianism - and therefore mostly take precedence on a constitutional level. In the common variant of liberal democracy, the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority - usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech or freedom of association.

The term democracy appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Classical Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy ("ἀριστοκρατία", "aristokratía"), meaning "rule of an elite". Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in antiquity, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as those in Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the Western world at the beginning of late antiquity. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in autocratic systems like absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy - oppositions inherited from ancient Greek philosophy. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.

Identity politics is a political approach wherein people of a particular gender, religion, race, social background, class or other identifying factors, develop political agendas that are based upon theoretical interacting systems of oppression that may affect their lives and come from their various identities. Identity politics centers the lived experiences of those facing various systems of oppression to better understand the ways in which racial, economic, sex-based, gender-based, and other forms of oppression are linked and to ensure that political agendas and political actions arising out of identity politics leave no one behind.

Contemporary applications of identity politics describe people of specific race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, economic class, disability status, education, religion, language, profession, political party, veteran status, and geographic location. These identity labels are not mutually exclusive but are in many cases compounded into one when describing hyper-specific groups, a concept known as intersectionality. An example is that of African-American, homosexual, women - who constitute a particular hyper-specific identity class.

See also: Laissez-faire capitalism

Laissez-faire (from French: "laissez faire", literally "let do") is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from or almost free from any form of economic interventionism such as regulation and subsidies. As a system of thought, laissez-faire rests on the axioms that the individual is the basic unit in society and has a natural right to freedom; that the physical order of nature is a harmonious and self-regulating system; and that corporations are creatures of the state and therefore the citizens must watch them closely due to their propensity to disrupt the Smithian spontaneous order.

These axioms constitute the basic elements of laissez-faire thought. Another basic principle holds that markets should be competitive, a rule that the early advocates of laissez-faire always emphasized. With the aims of maximizing freedom and of allowing markets to self-regulate, early advocates of laissez-faire proposed an impôt unique, a tax on land rent (similar to Georgism) to replace all taxes that they saw as damaging welfare by penalizing production.

Proponents of laissez-faire argue for a complete separation of government from the economic sector. The phrase laissez-faire is part of a larger French phrase and literally translates to "let [it/them] do", but in this context the phrase usually means to "let it be" and in expression "laid back." Although never practiced with full consistency, laissez-faire capitalism emerged in the mid-18th century and was further popularized by Adam Smith's book The Wealth of Nations. It was most prominent in Britain and the United States during this period but both economies became steadily more controlled throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. While associated with capitalism in common usage, there are also non-capitalist forms of laissez-faire, including some forms of market socialism.

The left-right political spectrum is a system of classifying political positions characteristic of left-right politics, ideologies and parties with emphasis placed on issues of social equality and social hierarchy. In addition to positions on the Left and on the Right, there are centrists or moderates who are not strongly aligned with either extreme. There are those who view the left-right political spectrum as overly simplistic, and who reject this method of classifying political stands, suggesting instead some other system, such as a two-dimensional rather than a one-dimensional description.

On this type of political spectrum, left-wing politics and right-wing politics are often presented as opposed, although a particular individual or group may take a left-wing stance on one matter and a right-wing stance on another; and some stances may overlap and be considered either left-wing or right-wing depending on the ideology. In France, where the terms originated, the left has been called "the party of movement" and the right "the party of order."

Liberalism is a political philosophy and moral philosophy based on liberty, consent of the governed, and equality before the law. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but they generally support individual rights (including civil rights and human rights), democracy, secularism, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, and a market economy. Yellow is the political colour most commonly associated with liberalism.

Liberalism became a distinct movement in the Age of Enlightenment, when it became popular among Western philosophers and economists. Liberalism sought to replace the norms of hereditary privilege, state religion, absolute monarchy, the divine right of kings, and traditional conservatism with representative democracy and the rule of law. Liberals also ended mercantilist policies, royal monopolies, and other barriers to trade, instead promoting free trade and marketization. Philosopher John Locke is often credited with founding liberalism as a distinct tradition, based on the social contract, arguing that each man has a natural right to life, liberty and property, and governments must not violate these rights. While the British liberal tradition has emphasized expanding democracy, French liberalism has emphasized rejecting authoritarianism, and is linked to nation-building.

Leaders in the British American Revolution of 1688, the American Revolution of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789 used liberal philosophy to justify the armed overthrow of royal tyranny. Liberalism started to spread rapidly especially after the French Revolution. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in nations across Europe and South America, whereas it was well-established alongside republicanism in the United States. In Victorian Britain, it was used to critique the political establishment, appealing to science and reason on behalf of the people. During 19th and early 20th century, liberalism in the Ottoman Empire and Middle East influenced periods of reform such as the Tanzimat and Al-Nahda, as well as the rise of constitutionalism, nationalism, and secularism. These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis within Islam, which continues to this day, leading to Islamic revivalism. Before 1920, the main ideological opponents of liberalism were communism, conservatism, and socialism - but liberalism then faced major ideological challenges from fascism and Marxism-Leninism as new opponents. During the 20th century, liberal ideas spread even further, especially in Western Europe, as liberal democracies found themselves as the winners' in both world wars.

In Europe and North America, the establishment of social liberalism (often called simply liberalism in the United States) became a key component in the expansion of the welfare state. Today, liberal parties continue to wield power and influence throughout the world. The fundamental elements of contemporary society have liberal roots. The early waves of liberalism popularised economic individualism while expanding constitutional government and parliamentary authority. Liberals sought and established a constitutional order that prized important individual freedoms, such as freedom of speech and freedom of association; an independent judiciary, and public trial by jury; and the abolition of aristocratic privileges. Later waves of modern liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights. Liberals have advocated gender and racial equality in their drive to promote civil rights and a global civil rights movement in the 20th century achieved several objectives towards both goals. Other goals often accepted by liberals include universal suffrage, and universal access to education.

Source: Wikipedia, 2021-09-27

Classical liberalism is a political ideology and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market, civil liberties under the rule of law with an emphasis on minarchism, economic freedom, and cultural liberalism. It was developed in the early 19th century, building on ideas from the previous century as a response to urbanization, and to the Industrial Revolution in Europe and North America.

Notable liberal individuals whose ideas contributed to classical liberalism include John Locke, Jean-Baptiste Say, Thomas Robert Malthus, and David Ricardo. It drew on classical economics, especially the economic ideas as espoused by Adam Smith in Book One of The Wealth of Nations, and on a belief in natural law, progress, and utilitarianism.

Until the Great Depression and the rise of social liberalismeconomic liberalism. As a term, classical liberalism was applied in retrospect to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from social liberalism.

Cultural liberalism (social liberalism in the United States) is a liberal view of society that stresses the freedom of individuals from cultural norms, and in the words of Henry David Thoreau is often expressed as the right to "march to the beat of a different drummer."

In following the harm principle, cultural liberals believe that society should not impose any specific code of behavior and they see themselves as defending the moral rights of nonconformists to express their own identity however they see fit as long as they do not harm anyone else. The culture wars in politics are generally disagreements between cultural progressives and cultural conservatives. The cultural progressives believe that the structure of one's family and the nature of marriage should be left up to individual decision and they argue that as long as one does no harm to others, no lifestyle is inherently better than any other.

Because cultural liberalism expresses the social dimension of liberalism, it is often referred to as social liberalism, especially in countries such as the United States. However, it is not the same as the broader political ideology known as social liberalism. In the United States, social liberalism describes progressive moral and social values or stances on socio-cultural issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage, as opposed to

Economic liberalism (also known as fiscal conservatism in the United States politics) is a political ideology and economic ideology based on strong support for a market economy and private property in the means of production. Economic liberals tend to oppose government intervention in the market when it inhibits free trade and open competition, but support government intervention to protect property rights and resolve market failures. Economic liberalism has been generally described as representing the economic expression of classical liberalism.

As an economic system, economic liberalism is organized on individual lines, meaning that the greatest possible number of economic decisions are made by individuals or households rather than by collective institutions or organizations. An economy that is managed according to these precepts may be described as liberal capitalism or a liberal economy.

Economic liberalism is associated with markets and private ownership of capital assets. Historically, economic liberalism arose in response to mercantilism and feudalism. Today, economic liberalism is also considered opposed to non-capitalist economic orders such as socialism and planned economies. It also contrasts with protectionism because of its support for free trade and open markets.

Economic liberals commonly adhere to a political and economic philosophy which advocates a restrained fiscal policy and the balancing of budgets, through measures such as low taxes, reduced government spending, and minimized government debt. Free trade, deregulation of the economy, lower taxes, privatization, labour market flexibility, and opposition to trade unions. Economic liberalism follows the same philosophical approach as classical liberalism and fiscal conservatism.

Liberalism in the United States ("modern liberalism") is a political philosophy and moral philosophy based on concepts of unalienable rights of the individual. The fundamental liberal ideals of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, the separation of church and state, the right to due process, and equality under the law are widely accepted as a common foundation of liberalism. It differs from liberalism worldwide because the United States has never had a resident hereditary aristocracy, and avoided much of the class warfare that characterized Europe. According to Ian Adams, "all U.S. parties are liberal and always have been. Essentially they espouse classical liberalism, that is a form of democratized Whig constitutionalism plus the free market. The point of difference comes with the influence of social liberalism" and the proper role of government.

Modern liberalism includes issues such as same-sex marriage, reproductive rights and other women's rights, voting rights for all adult citizens, civil rights, environmental justice, and government protection of the right to an adequate standard of living. National social services such as equal educational opportunities, access to health care and transportation infrastructure are intended to meet the responsibility to promote the general welfare of all citizens as established by the Constitution of the United States. Some liberals - who call themselves classical liberals, fiscal conservatives, or libertarians - endorse fundamental liberal ideals, but they diverge from modern liberal thought, claiming that economic freedom is more important than equality, and that providing for general welfare as enumerated in the Taxing and Spending Clause of the Constitution of the United States exceeds the legitimate role of government.

Since the 1930s, the term liberalism is usually used without a qualifier to refer to social liberalism, a variety of liberalism that endorses a regulated market economy and the expansion of civil and political rights, with the common good considered as compatible with or superior to the freedom of the individual. This political philosophy was exemplified by Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies, and later Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society. Other accomplishments include the Works Progress Administration, and the Social Security Act in 1935, as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This variety of liberalism is also known in the United States as modern liberalism, to distinguish it from classical liberalism - from which it derived, along with modern conservatism.

Modern liberalism (in the United States often simply referred to as liberalism) is the dominant version of liberalism in the United States. It combines ideas of civil liberty and social equality, with support for social justice and a mixed economy.

Economically, modern liberalism opposes cuts to the social safety net and supports a role for government in reducing inequality, providing education, ensuring access to healthcare, regulating economic activity and protecting the natural environment. This form of liberalism took shape in the 20th century United States as the franchise and other civil rights were extended to a larger class of citizens. Major examples include Theodore Roosevelt's Square Deal and New Nationalism, Woodrow Wilson's New Freedom, Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, Harry S. Truman's Fair Deal, John F. Kennedy's New Frontier, and Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society.

In the first half of the 20th century, both major American parties had a

Neoliberalism (neo-liberalism) is a term used to describe the 20th-century resurgence of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism. A significant factor in the rise of conservative and libertarian organizations, political parties, and think tanks, and predominately advocated by them, it is generally associated with policies of economic liberalization, including privatization, deregulation, globalization, free trade, austerity, and reductions in government spending in order to increase the role of the private sector in the economy and society; however, the defining features of neoliberalism in both thought and practice have been the subject of substantial scholarly debate. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and a pejorative valence. In policymaking, neoliberalism often refers to what was part of a paradigm shift that followed the failure of the Keynesian consensus in economics to address the stagflation of the 1970s.

English speakers have used the term neoliberalism since the start of the 20th century with different meanings, but it became more prevalent in its current meaning in the 1970s and 1980s, used by scholars in a wide variety of social sciences as well as by critics. The term is rarely used by proponents of free-market policies. Some scholars have described the term as meaning different things to different people as neoliberalism has "mutated" into geopolitically distinct hybrids as it travelled around the world. Neoliberalism shares many attributes with other concepts that have contested meanings, including representative democracy. The definition and usage of the term have changed over time. As an economic philosophy, neoliberalism emerged among European liberal scholars in the 1930s as they attempted to revive and renew central ideas from classical liberalism as they saw these ideas diminish in popularity, overtaken by a desire to control markets, following the Great Depression and manifested in policies designed to counter the volatility of free markets, and mitigate their negative social consequences. One impetus for the formulation of policies to mitigate free-market volatility was a desire to avoid repeating the economic failures of the early 1930s, failures sometimes attributed principally to the economic policy of classical liberalism.

When the term entered into common use in the 1980s in connection with Augusto Pinochet's economic reforms in Chile, it quickly took on negative connotations and was employed principally by critics of market reform and laissez-faire capitalism. Scholars tended to associate it with the theories of Mont Pelerin Society economists Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and James M. Buchanan, along with politicians and policy-makers such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and Alan Greenspan. Once the new meaning of neoliberalism became established as a common usage among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of political economy. By 1994, with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and with the Zapatistas' reaction to this development in Chiapas, the term neoliberal entered global circulation. Scholarship on the phenomenon of neoliberalism has grown over the last few decades.

Social liberalism, also known as left liberalism in Germany, new liberalism in the United Kingdom, modern liberalism in the United States, and progressive liberalism in Spanish speaking countries is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses a social market economy within an individualist economy and the expansion of civil and political rights. Under social liberalism, the common good is viewed as harmonious with the freedom of the individual.

Social liberal policies have been widely adopted in much of the world. Social liberal ideas and parties tend to be considered centrist or center-left. A social liberal government is expected to address economic and social issues such as poverty, welfare, infrastructure, health care, education, and the climate using government intervention whilst also emphasizing the rights and autonomy of the individual.

In the United States, the term social liberalism may sometimes refer to progressive stances on sociocultural issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage. as opposed to

Libertarianism (from French: libertaire, "libertarian"; from Latin: libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy and political movement that upholds liberty as a core principle. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, emphasizing free association, freedom of choice, individualism, and voluntary association. Libertarians share a skepticism of political authority and state power, but some libertarians diverge on the scope of their opposition to existing economic systems and political systems. Various schools of libertarian thought offer a range of views regarding the legitimate functions of state and private power, often calling for the restriction or dissolution of coercive social institutions. Different categorizations have been used to distinguish various forms of libertarianism. Scholars distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left-right or socialist-capitalist lines.

Libertarianism originated as a form of left-wing politics such as authoritarianism and anti-state socialists like anarchists, especially social anarchists, but more generally libertarian communists / libertarian Marxists and libertarian socialists. These libertarians seek to abolish capitalism and private ownership of the means of production, or else to restrict their purview or effects to usufruct property norms, in favor of common ownership or cooperative ownership and management, viewing private property as a barrier to freedom and liberty. Left-libertarian ideologies include anarchist schools of thought, alongside many other anti-paternalist and New Left schools of thought centered around economic egalitarianism, as well as geolibertarianism, green politics, market-oriented left-libertarianism, and the Steiner-Vallentyne school.

In the mid-20th century, right-libertarian proponents of anarcho-capitalism and minarchism co-opted the term libertarian to advocate laissez-faire capitalism and strong private property rights such as in land, infrastructure and natural resources. The latter is the dominant form of libertarianism in the United States, where it advocates civil liberties, natural law, free-market capitalism, and a major reversal of the modern welfare state.

Left-libertarianism, also known as egalitarian libertarianism, left-wing libertarianism or social libertarianism, is a political philosophy and type of libertarianism that stresses both individual freedom and social equality. Left-libertarianism represents several related yet distinct approaches to political and social theory. In its classical usage, it refers to anti-authoritarian varieties of left-wing politics such as anarchism, especially social anarchism, whose adherents simply call it libertarianism. In the United States, it represents the left-wing of the libertarian movement and the political positions associated with academic philosophers Hillel Steiner, Philippe Van Parijs, and Peter Vallentyne that combine self-ownership with an egalitarian approach to natural resources. This is done to distinguish libertarian views on the nature of property and capital, usually along left-right or socialist-capitalist lines.

While maintaining full respect for personal property, socialist left-libertarians are opposed to capitalism and the private ownership of the means of production. Left-libertarians are skeptical of, or fully against, private ownership of natural resources, arguing in contrast to right-libertarians that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights and maintain that natural resources should be held in an egalitarian manner, either unowned, or owned collectively. Those left-libertarians who are more lenient towards private property support different property norms and theories such as usufruct, or under the condition that recompense is offered to the local community or even global community, such as the Steiner-Vallentyne school.

Left-wing market anarchism (or market-oriented left-libertarianism), including Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's mutualism, and Samuel Konkin III's agorism, appeals to left-wing concerns such as class, egalitarianism, environmentalism, gender, immigration, and sexuality within the paradigm of free-market anti-capitalism. Although libertarianism in the United States has become associated to classical liberalism and minarchism, with right-libertarianism being more known than left-libertarianism, political usage of the term until then was associated exclusively with anti-capitalism, libertarian socialism, and social anarchism and in most parts of the world such an association still predominates.

Libertarianism in the United States is a political philosophy and political movement promoting individual liberty. According to common meanings of

Broadly, there are four principal traditions within libertarianism, namely;

the libertarianism that developed in the mid-20th century out of the revival tradition of classical liberalism in the United States after liberalism associated with the New Deal;

the libertarianism developed in the 1950s by anarcho-capitalist author Murray Rothbard, who based it on the anti-New Deal Old Right and 19th-century libertarianism and American individualist anarchists such as Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner, while rejecting the labor theory of value in favor of Austrian School economics and the subjective theory of value;

the libertarianism developed in the 1970s by Robert Nozick and founded in American and European classical liberal traditions; and,

the libertarianism associated to the Libertarian Party which was founded in 1971, including politicians such as David Nolan and Ron Paul.

Compared to left-libertarianism, right-libertarianism - associated with people such as Murray Rothbard and Robert Nozick - is the dominant form of libertarianism in the United States. According to David Lewis Schaefer, Robert Nozick's book Anarchy, State, and Utopia has received significant attention in academia.

Left-libertarianism is associated with the left-wing of the modern libertarian movement and more recently to the political positions associated with academic philosophers Hillel Steiner, Philippe Van Parijs, and Peter Vallentyne - that combine self-ownership with an egalitarian approach to natural resources. Left-libertarianism is also related to anti-capitalist, free-market anarchist strands such as left-wing market anarchism (referred to as market-oriented left-libertarianism, to distinguish itself from other forms of libertarianism).

Libertarianism includes anarchist and libertarian socialist tendencies, although they are not as widespread as in other countries. Murray Bookchin, a libertarian within this socialist tradition, argued that anarchists, libertarian socialists and the left should reclaim libertarian as a term, suggesting these other self-declared libertarians to instead rename themselves propertarians.

Although all libertarians oppose government intervention, there is a division between:

anarchist or socialist libertarians - as well as anarcho-capitalists such as Murray Rothbard and David D. Friedman - who adhere to the anti-state position, viewing the state as an unnecessary evil;

minarchists - such as Robert Nozick - who recognize the necessary need for a minimal state (often referred to as a night-watchman state); and,

classical liberals who support a minimized small government, and a major reversal of the welfare state.

The major libertarian party in the United States is the Libertarian Party, but libertarians are also represented within the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, while others are independent. Through twenty polls on this topic spanning thirteen years, Gallup found that voters who identify as libertarians ranged from 17 to 23% of the American electorate. However, a 2014 Pew Poll found that 23% of Americans who identify as libertarians have little understanding of libertarianism. Yellow, a political color associated with liberalism worldwide, has also been used as a political color for modern libertarianism in the United States. The Gadsden flag, a symbol first used by American revolutionaries, is frequently used by libertarians and the libertarian-leaning Tea Party movement.